Springtime brought the death of the dinosaurs 66 million years ago, a new peer-reviewed study has found.

The study, published in the peer-reviewed journal Scientific Reports, was conducted by an international team from Florida Atlantic University and the University of Manchester.

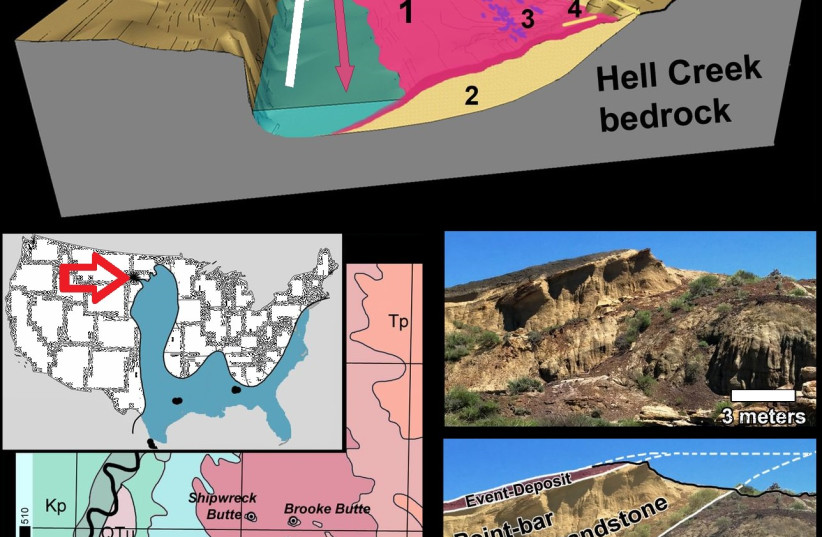

The team examined the Tanis research site in North Dakota, one of the most highly detailed sites along the boundary between the Cretaceous and Paleogene eras (K-Pg) created by the asteroid extinction event that wiped out the dinosaurs, along with 75% of life on earth.

"This unique site in North Dakota had yielded a wealth of new and exciting information," said Anton Oleinik, a co-author of the paper and an associate professor at FAU, in an article on FAU's website. "Field data collected at the site, after hard work that went into analyzing it, provided us with new incredibly detailed insight of not only what happened at the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary, but also exactly when it happened. It is nothing short of amazing how multiple lines of independent evidence suggested so clearly what time of the year it was 66 million years ago when the asteroid hit the planet."

"This project has been a huge undertaking but well worth it," said senior author Robert DePalma, an adjunct professor at FAU and PhD student at the University of Manchester, in a University of Manchester press release. "For so many years we’ve collected and processed the data, and now we have compelling evidence that changes how we think of the KPg event, but can simultaneously help us better prepare for future ecological and environmental hazards."

While previous research has shown that the Chicxulub asteroid impact that caused the mass extinction event hit the Yucatan Peninsula 66 million years ago, the finer details of what happened between the asteroid impact and the mass extinction are still unknown.

In a study in 2019, a team led by DePalma used multiple lines of evidence, including radiometric dating, stratigraphy, fossilized remains of biological marker species and a layer of iridium-rich clay to document that the Tanis site contains the only impact-caused vertebrate mass-death assemblage at the K-Pg boundary. The team believes that the layer at the Tanis site documents the first hours of the asteroid impact.

The 2019 study found that a massive surge of water rapidly deposited sediments that locked in the evidence used for the latest study. The densely packed collection of plants, animals, trees and material ejected by the impact helped them refine details about the extinction event and the ecosystem destroyed by it.

The time of year plays an important role in many biological functions, such as reproduction, feeding strategies and seasonal dormancy, among other things, meaning that the season during which the extinction event happened could affect how it impacted the world.

The team used growth lines preserved in the fossilized bones of fish that died in the event triggered by the impact. The growth lines provide a record of the fish life histories, allowing the team to deduce the season in which they died from the bony growth pattern.

The unique structure and pattern of the growth lines showed that the fossilized fish died during the Spring-Summer growth season. Isotopic analysis of the growth lines provided independent confirmation of the findings, showing a yearly seasonally-driven oscillation that ended during the Spring-Summer growth.

The team used additional lines of evidence to back up their findings, including examining juvenile fossilized fish with help from cutting-edge Synchrotron-Rapid-Scanning X-Ray Fluorescence (SRS-XRF) at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL). This provided a new way to date the seasonal variation observed in fossils at the site. By comparing the sizes of the youngest fish to the growth rates of similar modern fish, the team was able to predict how long after hatching they were buried at the site.

“Animal behavior can be a pretty powerful tool, so we overlapped even more evidence, this time of seasonal insect behavior, such as leaf-mining and mayfly activity," said Loren Gurche, a co-author on the study, in the University of Manchester press release. "They all matched up…everything points to the fact that the impact happened during the northern hemisphere equivalent of Spring to Summer months."

The Tanis site has generated excitement, as well as controversy, in recent years, hitting a rocky start when the first findings at the site by DePalma were unveiled in a New Yorker article in March 2019 titled "The day the dinosaurs died."

The article generated controversy in part because some of the details mentioned in it were not mentioned in the scientific paper that was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science after the New Yorker article.

In April 2019, Kirk Johnson, director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, told Smithsonian Magazine that it was "unfortunate" that many aspects of the study appeared only in the New Yorker article and not in the paper.

"This is a sloppy way to conduct science and it leaves open many questions. At the present moment, interesting data are presented in the paper while other elements of the story that could be data are, for the moment, only rumors," said Johnson.

The fact that the information about the site appeared in a magazine before a scientific paper broke the norm in the field, sparking skepticism, but many experts still noted that Tanis does seem to be an exceptional site. Most articles at the time agreed that the site was definitely unique and provided a great opportunity to understand more about the asteroid extinction event.

Another point that sparked criticism at the time is the fact that Tanis is on private land and DePalma has an exclusive long-term excavation lease at the site, according to the New Yorker article. DePalma also retains "oversight" of the management of unearthed fossils, instead of allowing them to be freely studied at institutions.

Since DePalma is not receiving federal support, he has to pay for his expenses himself. In order to help with the costs, he mounts fossils, does reconstructions and casts and sells replicas for museums, private collectors and other clients.

"It’s unethical and unprofessional," said Jessica Theodor, professor of biological sciences at the University of Calgary, to Maclean's magazine. "If you donate your specimens to a repository, the whole point is that other people need to be able to verify your claims. If you’re trying to restrict access to them, that’s really problematic."

One geologist who asked not to be named told Science magazine that DePalma's "line between commercial and academic work is not as clean as it is for other people."