At first there was a kind of euphoria when the war broke out. It was not a surprise. We had been preparing for it. The PLO rockets had been coming for over a year. When it was finally launched in June 1982, we were itching to fight. But as it bogged down, casualties mounted and initial war plans to conquer a swath of south Lebanon soon turned into a grand plan to finally expel the Palestine Liberation Organization out of Lebanon. It became a quagmire that led to an 18-year occupation that culminated in a humiliating retreat in the night.

But back in West Beirut, on the eve of Rosh Hashanah, September 18, 1982, we moved toward the corner at dawn. It was like walking down any city street, with the sidewalks, doorways and the storefronts. Only now, our combat boots crushed the crunchy shards of broken glass. Live wires dangled from above, sizzling and crackling. A few parked cars were soldering wrecks. Dust filled the Mediterranean air, filtering the sun as it rose over Mount Lebanon into the port of Beirut.

We shuffled along in single file, our assault rifles loaded, fingers on the triggers. One of our 43,000 kg. Merkava battle tanks rumbled along in the road next to us. The monster shook the ground and made the walls shudder.

Its visceral power calmed me.

But the thick air choked us. The heaving rat-tat-tat of our comrades’ guns sounded nonchalantly from somewhere down the block. But when the distinct guttural sound of a Kalashnikov rifle spraying its thick 7.62mm rounds echoed above, we knew our Palestinian enemy was real and he was waiting for us.

Half a dozen Israeli jet fighters streaked across the sky, visible above between the multi-story buildings. The warplanes were very high and howling away into the gray haze toward the Mediterranean Sea. Yellow streaks of anti-aircraft fire followed but did not quite reach them.

We scuttled up to the corner of a huge boulevard. This was it. My 21-year-old lieutenant Yoav led the way, followed by the radio man. Then Yehuda, a linebacker of a man heaving his heavy machine gun, and then me with my rifle and grenades.

I looked back. Behind us was the rest of my platoon and behind them my Nahal 906th battalion, fresh from non-commissioned officers’ course. And behind them, an entire brigade or more of the IDF, all waiting for the battle to begin. It was as if this mighty juggernaut was waiting... for us. I turned back around. The sergeant was signalling with his hand: “Forward.” I lifted my booted foot. I turned the corner and literally stepped into our war.

A few weeks before, we had been enforcing the siege on West Beirut until Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat shipped out with the bulk of his forces under United Nations protection. The future looked good for Lebanon and Israel.

Bashir Gemayel, a young, charismatic, Maronite commander, had just been elected president of Lebanon. He was courageous enough to engage with Israel and then-prime minister Menachem Begin ordered the IDF to pull its troops back. The last thing Israel wanted to do was capture the capital of an Arab country.

BUT LIKE a march of the follies, this is exactly what our orders were when Gemayel was assassinated before he could take office and implement his treaty with Israel. Enter Beirut from the north, march through the port and open the main north-south artery and meet up with a division heading from the southern neighborhoods.

“Bashir’s just been assassinated,” said one of my platoon buddies, while we were on maneuvers in the Galilee.

“What does that mean?”

“We’re going in. We’re going back to Beirut.”

I was filled with a twisted sense of guilt over an inexplicable inner urge to go to battle. It was like waiting for a hurricane.

It’s difficult to explain the thrill of anticipation of combat or a storm to healthier minds. I wasn’t feeling any pangs of objection about heading back innocently into a war zone we had absolutely no idea about – quite the contrary.

The city was swarming with armed Christian Phalangists and Druse militias, not to mention the castrated Lebanese Army and the remnants of the PLO. Didn’t we just chase them out of Beirut? And didn’t they leave amid an amazing fireworks display made of tracer bullets streaking across the sky, as we sat on the rooftops of the shacks in the Burj el Burajne refugee camp watching it all, actually believing then that the war, dubbed by the government Peace for the Galilee, might actually be over? And now, Bashir Gemayel was dead.

Begin ordered the Israeli army to conquer West Beirut. I was on a rickety passenger bus commandeered by the military, driving at night to the front line. I watched, incredulously, the Beirutis in their lit-up living rooms watching TV and eating, totally oblivious of the columns of Israeli soldiers flowing by their front doors. I kept wondering when we were going to get off these vulnerable buses – the old kind with short back seats – and get into the safer APCs (armoured personnel carriers)? We never did.

We could see that we were heading north, circumventing the city to the east.

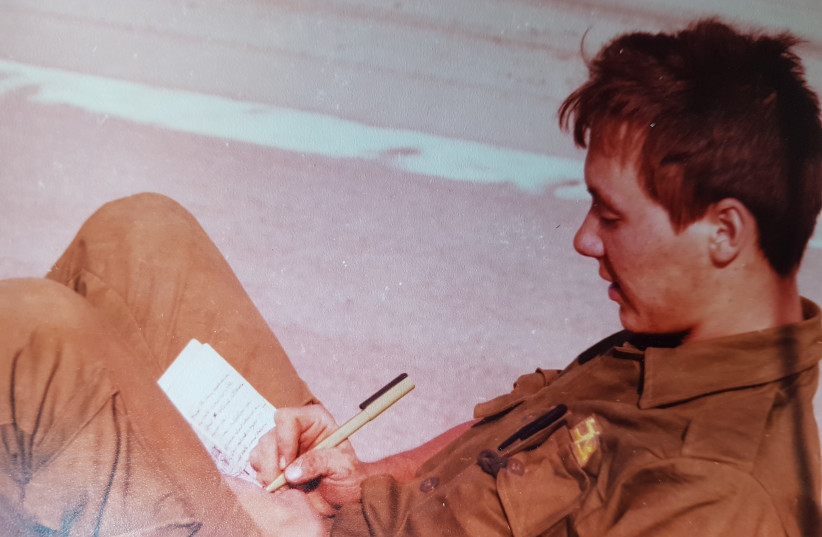

All we had was our webbing and battle gear: flak jackets, helmets, ammo belts, the one uniform we were wearing and boxes of ammunition. We had no personal equipment. In my webbing I stuffed seven full ammo clips. We had two grenade pouches. I took one out and latched it to the back of my belt. In its place I put the small Kodak Instamatic camera I had bought three years before in some Mississippi River town when working on the Delta Queen steamship.

We were gathered at the port of Beirut between towering cement grain silos. The wharves were empty of ships. The silos served as a sort of wall protecting us from mortar fire from the western neighborhood, Ras Beirut (“Tip of Beirut,” an upscale residential neighborhood of Beirut). These very same silos would be blown to bits in a massive mysterious explosion, in 2020.

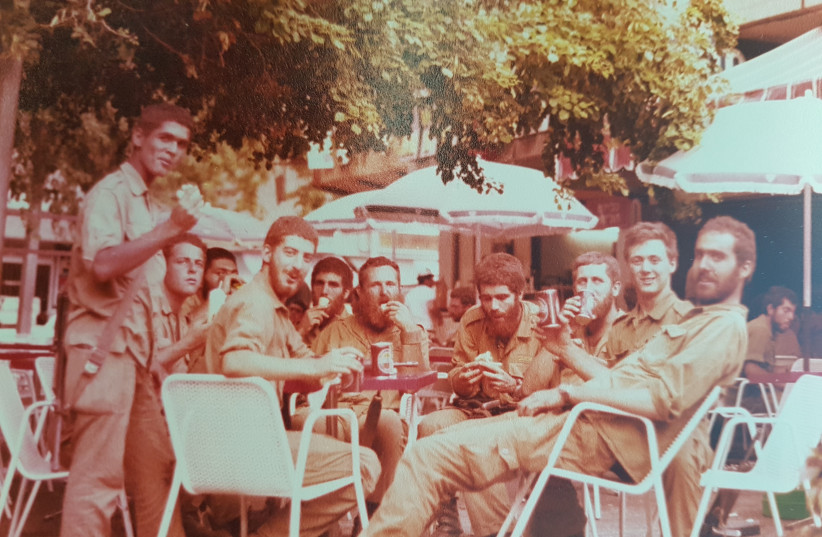

Some soldiers loaded up on extra grenades, others stuffed their pouches with candy bars. Across the bay the port of Junieh was lit up like a county fair. Jets screamed overhead. The other battalions of our NCO brigade, the crack Golani and elite Paratroopers, started rendezvousing with us. Downtown Beirut was spread out before us with its scores of multistoried buildings and canyon-like streets.

Peace for the Galilee

WE HAD a final briefing from a battalion commander and then the division commander Brig.-Gen. Amos Yaron showed up on the front and our filthy battalion gathered around him. Sitting atop a few tanks, leaning against ammo crates, we heard him out.

This was the final drive to ensure Peace for the Galilee, he told us in his hoarse voice. No one ever called it that and this summer 1982 war would later be known as the Lebanon War. After history repeated itself (there was a Second Lebanon War in the summer of 2006), it was known as the First Lebanon War.

The general warned tough fighting awaited us in a city, but said it was necessary.

And then something remarkable happened, which revealed the unique relationship between the ranks in the Israeli army, where strict hierarchies and unwavering obedience to superiors crumbles as part of the undisciplined Israeli culture.

“Go to hell,” said one of the company commanders. “You are sending us to our deaths.”

“Screw you,” another officer told the general to his face.

“We haven’t even trained in taking two-story houses, let alone 12-story buildings,” said a lieutenant.

“It’ll be a death trap.”

Suddenly, all the officers spoke up.

“Just call in the artillery.”

“Why don’t we just poison the water supply?”

“What about our air force, Yaron?”

This was an egalitarian army where even generals are addressed by their first names and where every soldier was drilled that if you see something wrong, you say so. It came, I suppose, from the abhorrence of Germans saying they were only obeying orders when they murdered innocent Jews.

Yaron – who would in two days’ time face the dilemma of ordering military support for Christian Phalangist militias as they rampaged through the Palestinian refugee camps of Sabra and Shatilla – tried to speak, became flustered and finally muttered something about it being a Zionist and national mission to clear the PLO scum from this gorgeous city once and for all. This was insane, I thought. Yet despite all this, something manly deep inside me was highly aroused and urged me on to battle.

The last thing a conventional army wants is to engage the enemy in a city. It robbed us of our overwhelming advantages in weaponry and technology.

Radios often did not work and the best surveillance equipment cannot always find enemies in alleyways. This was 1982, pre-internet and satellite communications. We still trained with flags, for chrissake.

THE PLACARDS with plastic-covered aerial photos of downtown meant nothing to us. Dawn was coming and we set out. We followed one of the other battalions. Our captain, Ilan, tall, blond and with a chiseled face like an Aryan, led the way. We headed west along a main road.

Here and there were vehicles that had been run over and squashed by tanks.

A man, maybe in his 30s, quietly clutched the steering wheel of a white two-door compact Renault. The top of his head was missing from right above the eyeballs.

“Wrong place, wrong time,” quipped Lee James Stocker. American born-and–bred like me, Lee James was nearly two meters tall with a Burt Reynolds mustache. He chewed tobacco, Copenhagen, a habit we sometimes shared but our fellow Israeli company mates could never comprehend.

We took point, leading what I found out later was a brigade column. We started moving quickly down the street, leapfrogging from doorway to doorway, cover to cover. It was getting brighter. A Merkava tank in the street advanced and occasionally let off a round. No one else fired.

The wiry, crazy battalion commander, his long, biblical beard split into two by his chin strap, walked down the street, back and forth, cool as a cucumber.

“Who was this fearless guy?” we wondered. Then the RPGs started hitting.

We were moving into a heavily built-up area and the rockets whooshed down. Some hit the street and exploded. One blew up and its fins sailed off, as if in slow motion, toward the other side of the street. Lee James saw it coming and ducked. A split second later, a hunk of shrapnel the size of a pelican smacked into the telephone pole behind him. He saw me and I swear, he spat out tobacco, grinned and gave me the thumbs up.

Just about this time we had come to a small T-junction.

From down the street, flashes of light sparked out of dark windows. Simultaneously, there was the distinctive crack of bullets passing overhead and splattering on the wall between myself and Nir, the soldier behind me. We both jumped down and out of the way. The soldiers on the other side of the road returned fire. Someone had decolorized the world.

Everything was gray: The sky was gray. The buildings were gray. The streets were gray. The smoke was gray.

Before we had time to think about this near miss too much, the lieutenant called us forward. We had come to a large junction. Someone in the buildings across the street was firing RPGs at us.

Two Merkava tanks advanced with us. One drove into the kill zone in the junction and braked. As it swung down and came to that pause, it let go a round into the second story of the buildings and then reversed like crazy. As it was reversing, the second tank came up adjacent to it, turned its cannon and fired another round. It was pure synchronicity.

THE C.O. called up Yehuda and ordered him to open fire into the windows kitty-corner to us. He took some shots himself. Whoosh! An RPG hit the tank, slipped underneath it and exploded. The hatch opened and the soldier inside calmly tossed out spent shells.

Amazing. This Israeli invention, I thought, is totally impervious to Soviet-made RPGs.

More RPGs hit and the lieutenant, apparently wounded, skipped back. The captain on the other side did the same. The heavy machine-gunner on the other side of the road started walking back, very slowly.

As he walked, the front of his fatigues at thigh-level started getting really, really dark and the color just started fading from his face. He was walking slower and slower, and in slow motion he fell to his knees, and then on his face. A chunk of shrapnel had cut into his femoral artery and he was bleeding out quickly.

Someone grabbed him and seconds later an APC whipped up the street, snapped a tight U-turn, dropped the back ramp and medics dragged him in. It couldn’t have taken more than 60 seconds.

A soldier a few guys back started to freak out. He yanked off his helmet, sat down in the alley and just started crying his head off. The sergeant slapped him a few times. I saw it was that big talker from the other platoon, the gung-ho geezer who was itching to go to war.

I knew I definitely did not want to cross this intersection.

We tossed a bunch of smoke grenades and ran like hell, across and into the courtyard of a large unfinished building on the other side. The adrenaline was flowing so hard I leaped/flew/danced across and didn’t feel the weight of the equipment on my back. We jumped behind walls till we got to the lobby of a shell of a building. Inside were gathered troops from the Lebanese Army. Why we didn’t shoot them I don’t know. We were all very cautious about opening fire.

An English-speaking officer from the Lebanese Army approached us and asked, “Are you taking many casualties?” He sounded almost too compassionate, I thought. I wasn’t sure what he wanted to hear. Yes, the Jews are suffering? Or not? And why were they not fighting? What was their role in all of this? Was he a Christian or a Muslim or a Druse? They watched us come in.

It turned out that Capt. Ilan had radioed that he, the lieutenant and some other soldiers had been wounded, slightly. We had confidence in him not that he would win the battle but that he would get us home. The battalion commander angrily switched our company with another company.

We were ordered to climb the building and take over its top floor. It was a shell. No elevator. We started climbing. Five floors, 10 floors, 16 floors. It was getting tiring. Thirty-nine floors total, the tallest building in Beirut. The view from the top was tremendous. It offered a bird’s-eye view at all the street battles going on below. Smoke billowed up from various quarters of the city. To the north was the port we had started out from. To the south were endless streets.

“Keep away from the edges,” the lieutenant scolded us. He had a slight shrapnel wound in his leg and was spoiling for action. We took up lookout posts. I noticed the building next to us had a huge red cross painted on the roof. A hospital? From this hospital my officer said he detected a sniper. He pulled out his M-16 and took a couple of shots at him. And the guy on the next roof scrambled for cover and then lay still in a pool of blood.

A FEW hours later we got orders to continue moving out. We came all the way down the stairs. It took a long time. We parted with the Lebanese soldiers. Their officer wished us luck.

By now, the fighting was a few blocks southward.

Troops were spread out along both sides of the street. Tanks were moving back and forth. I was amazed at the beauty and wealth of this city. The buildings were faced with marble and the cars were all fancy, mostly German made. Occasionally, we’d come upon a crushed vehicle or a blown out shop front.

And most bizarrely, with the shooting going on just a couple of blocks ahead, an enterprising Lebanese man came out and set up a table with cigarettes and other luxury items like cologne and liquor for sale. It was surreal. One could see the effect living in a war zone for years could have on people. Apathetic isn’t the right word. They were just no longer frightened of the battles anymore. It was like Mardi Gras. People began to line their porches and sidewalks, as if to watch Rex or Como or some other carnival parade pass by. I found myself dodging not only the burning cars and blown up shops, but also the crowds of women tossing rice on us, a sign we were finally seen as liberators.

The people cheered us as we scrambled past. I felt it was like in the old movie reels from the Second World War when US troops liberated Rome. I just didn’t understand. Were these the same people who had been defying us not two weeks before? At one point, kids started coming out. We shooed them away. And then a man came to us bearing a platter full of fruits and a pitcher with ice water. Yes, ice.

Where did he get ice from in this war-torn city? He held it above his head and proclaimed in perfect English, “The Lebanese people are a very hospitable people, a very friendly people. But you and everyone else must leave our country.”

“Absolutely,” I agreed. “Just give us the ice water.”

But I was leery. I suspected it might be poisoned, so I made him drink it first. He seemed insulted, but he did it, and we all followed.

Night was falling and the Lebanese were retreating back to their apartments. Soon enough, the streets were empty again and only we Israeli soldiers were left in the dusty dusk. We entered an apartment building and chased the people to their neighbors upstairs and commandeered a floor for the night.

Before dawn, we were on the streets. Word came down that we were to take over a headquarters of the PLO.

Intelligence said it was abandoned, but maybe booby-trapped.

My squad was the first in. We quickly rushed to the top of the six-story building, as the urban warfare manual said, and worked our way downward. The top floor had a plush boardroom with a huge walnut table and fancy leather chairs. There was a poster or photo of former Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser on every floor.

This was the headquarters of al-Mourabitoun, a Muslim socialist militia linked with the PLO. A few of us gathered around the boardroom where terrorist raids were likely planned and posed with some of the booty: a PLO flag and some photos. Someone held up a framed picture of Nasser upside down, just like in the Life magazine photos of the victorious Israeli soldiers in the 1967 Six Day War.

THE BASEMENT was filled with supplies. We hadn’t eaten for two days, at least. All we could find were cookies and Balkan honey. I immediately ripped open the cellophane and stuffed them into my mouth.

They were thankfully still fresh. I shared them with the rest of the platoon.

Shooting was sporadic in the city now. Someone mentioned it was the eve of Rosh Hashanah. The company master sergeant mysteriously showed up at dusk.

He didn’t have any rations. Instead, he managed to present us with a crate of apples, of all things. I brought up the Balkan honey from the basement. In an inner, windowless room, the platoon gathered. Our uniforms were so filled with dried sweat and mud they could probably have stood upright by themselves.

Benjy, the only religiously observant soldier in the platoon, miraculously produced two candles and lit them for the New Year. We tried to sing some New Year songs, but there was a place in every soldier’s mind where he’d rather be.

We sang: “The whole entire world Is just a very narrow bridge and the most important thing is not to be afraid at all.”

The memories of past Rosh Hashanahs ran through everyone’s mind. How ironic it was for this symbolic holiday of transition to fall just at this time of bittersweet transformation in our lives. Our Lebanese apples dipped in Balkan honey assured us of the sweetness of the coming New Year. But could we be sure? Here we were crossing that bitter stage in life from soldiers to veterans; from untested, wound-up trainees to proven fighters.

On this New Year’s, we almost let ourselves be called soldiers. Perhaps, we were more survivors, but then, what’s the difference? With everyone lost in their own thoughts, we put out the candles, lest their light give us away to the night snipers, and drifted to our posts.

Tradition called for a Jew to blow the shofar for this holiday to welcome in the New Year. The only shofarot we heard were the cannons of the tanks firing, as we leaned our crusty backs against the wall of this terrorist headquarters in Beirut, eating Lebanese apples dipped in Balkan honey confiscated from the PLO. Corny but true.

Tekiya! Terua! The New Year began with a long, long night.

I had my transistor radio with me and somehow got it working with old batteries from a walkie talkie. I tuned in to Radio Monte Carlo. The sky filled with flares. Occasionally, we’d hear the crash of a fin of a 120 mm. mortar flare hitting a parked car or something in the streets. There were so many flares, it became too dangerous to stay on the roof.

We didn’t know what was going on. At one point the radio station began playing that spiritual “He’s got the whole world in His hands.” The flares, it turned out, were being fired by the IDF to give light to the Christian Phalangist militia, operating in two refugee camps a few blocks away. Their names would be etched in Middle Eastern history forever: Sabra and Shatilla.

Dawn finally came. We were ordered to get ready for a foot patrol. The sergeants were calling it a capture patrol. The idea was to go out in full regalia and circle around a couple of blocks to show our faces; that way, the Israeli army could say it had conquered the city.

WHO MAKES up these rules of engagement? I wondered.

This was suicide. Gunmen could shoot us down like sitting ducks from any apartment.

But it was a time of shock and awe, when the locals feared the mighty Israeli army. We set out. Going from doorway to doorway, cover to cover. But it got to be ridiculous, since the people started to crowd around us. Sometimes, the lieutenant would yell at them to get back. We were maneuvering around in a war zone on the ground floor, while on the balconies above us hordes of people, families, kids and adults watched it all like we were the featured floats in a victory parade.

That’s when rumors started to reach us that there had been a massacre.

A Beiruti strolled by bouncing a football. In his hand was a newspaper with photos of mounds of dead people.

“The Palestinians,” the young man smiled. “Good riddance.”

The Palestinian refugee camps of Sabra and Shatilla were just a few blocks away. We asked each other if it could be true. Were the Phalangists really such animals? All I wanted to do was get out of this enormously vulnerable situation.

We returned toward the PLO headquarters, which was now our base of operations. Meanwhile, someone had discovered a second basement underneath the first one, and it was filled to the brim with weapons. It turned out to be one of the largest hauls of contraband captured in the whole war. There were anti-aircraft guns, crates of Soviet-made AK-47s and one or two crates of bayonets. The CO told everyone we were allowed one each. “If the IDF doesn’t supply my boys with bayonets, then I will,” he proclaimed. I took two.

We continued to pillage the headquarters. Over a dozen semitrailers came in and we helped load them up till they were bursting with weapons. They even took the wooden table and desk from the boardroom.

Which general was going to decorate his office with this? I wondered.

Phalangist militia came by and we gave them some bayonets. They were a sleazy-looking lot, long-haired and unshaven. Evil.

“Arieh,” someone yelled a few days later. “They’re letting three of us go home for leave. You’re one of them, you lucky bastard. Get your gear together. You’re going home.”

ONLY IN Israel are the battle fronts so close that you can find yourself at home after a few hours on a bumpy ride in the back of an army truck. And so it was: one moment I was in an ugly urban war zone in some Arab capital on Rosh Hashanah, and the next, hitching a ride up the eucalyptus-lined lane to my rural kibbutz in southern Israel, the returning hero.

Scarcely had I showered off the literal layers of battle and Lebanese dirt than one of the kibbutz girls yelled for me to hurry.

“What for?”

“We’re going to Tel Aviv. To the protest. The antiwar protest.”

And so I joined 400,000 or so other Israelis that night at the Malachai Yisrael Square in probably the largest anti-war demonstration in the country’s history.

I was likely one of the very few people there who had come almost literally from Beirut, and Sabra and Shatilla. And yes, we were appalled by the massacre of the hundreds of Palestinians; yes, we had no business in this war; and yes, Israel had to leave Lebanon.

But that night, the words of Begin kept ringing in my ears: “When the goyim kill the goyim, the Jew gets the blame.”

“When the goyim kill the goyim, the Jew gets the blame.”

Menachem Begin

Covering the Israeli army, looking back in retrospect, it is easy to say what happened, but then, we didn’t know. I identified it as a turning point in Israel’s history. It was a war of choice, not one of an existential threat against the state. It wasn’t a surprise attack, like in 1973. It was a war Israel launched to take out the PLO.

It changed the psyche of Israel and people started to question the decisions being made more. It led to an 18-year-occupation of southern Lebanon and eventually the public opposition to it was a major factor in the decision by then-prime minister Ehud Barak to pull the army back into the international borders, in 2000.

When the IDF pulled out it was again euphoria. We military correspondents were incensed because, despite the promises of the IDF brass to be with the troops as they returned, alas the retreat was so hasty we didn’t have a chance. Nevertheless, a whole generation of Israeli soldiers fought through Lebanon and just short of 18 years after we first invaded, the last soldiers returned and the regional brigadier general, Benny Gantz, locked the gate. ■

The writer, a former defense correspondent for The Jerusalem Post, is currently the anchor for English news at KAN, Israel Public Radio.