In 1919, in the pamphlet “Prelude to Pogroms?” Alfred Wiener, who had served in the German Army during World War I, warned without reservation that “a mighty antisemitic storm has broken over us.”

Speakers on the streets “talk of plundering Jewish businesses”; leaflets accuse Jews of ritual murder “for the purpose of manufacturing goat sausages” and promise that Germany will free itself “completely and mercilessly, from these bloodsuckers.”

In the 1920s and ‘30s, Wiener worked for and then led the Central Association of Citizens of the Jewish Faith. An organization with regional offices all over the country, the “CV” held mass meetings; brought court cases against antisemitism, including one proving the Protocols of the Elders of Zion was a forgery; and assembled a voluminous archive of Nazi publications, policies, attitudes, and support. Following the appointment of Adolf Hitler as chancellor of Germany in 1933, Wiener relocated his family to Amsterdam, which he thought was a safe haven.

In Two Roads Home, Daniel Finkelstein (columnist at The Times, adviser to former British prime minister John Major, and a member of the House of Lords) tells the stories of the Wieners and the Finkelsteins, his maternal and paternal grandparents, the former victimized by the Nazis, the latter by Soviet Communists. Drawing on oral history, letters, diaries, and government records, Two Roads Home is, by turns, sobering, suspenseful, and inspiring.

Outlasting the Nazis and the Soviet Communists

Finkelstein captures the lived experiences of these two families in often haunting detail. An affluent iron and steel manufacturer and member of the Lwόw City Council, Dolu Finkelstein believed his Jewish identity was compatible with the multi-ethnic identity of modern Poland.

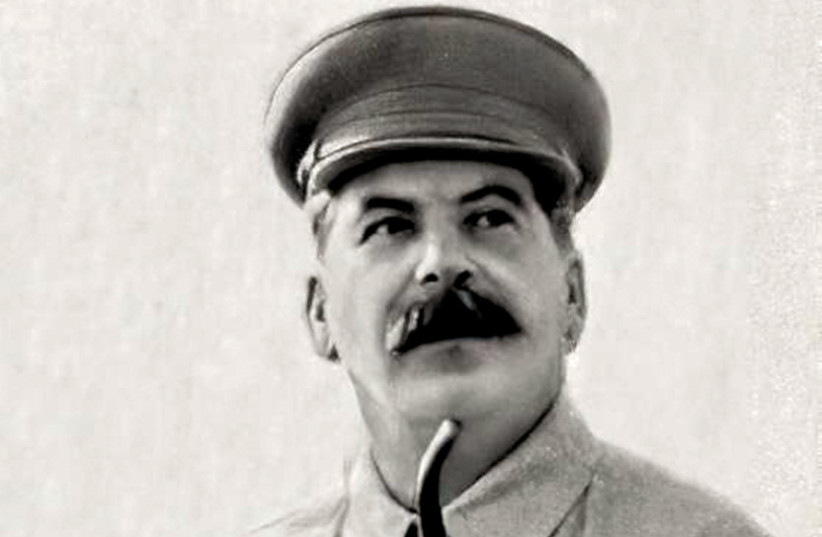

During World War II, however, Dolu was deported to Siberia as part of Stalin’s attempt to eliminate nationalists to facilitate the incorporation of Poland into the Soviet Union. Lusia, his wife, and their son Ludwik were sent to a forced labor camp in Kazakhstan. Their train provided almost no light, little air, not enough space to lie down, a hole to relieve themselves, and lots of lice.

Departure in April, Finkelstein reveals, may have saved their lives. Freezing weather killed thousands in winter, and the summer heat was just as deadly. Because they had been deported, not arrested, moreover, mother and son were able to receive letters and parcels of food from their relatives. Assigned to make adobe bricks out of cow dung, Lusia stole some dung to use as fuel to cook food and heat their hut.

THE WIENER family was separated as well. To prevent the Nazis from burning his archive, Alfred moved to London. During the war, he worked for British Intelligence and the US State Department. When the Low Countries were invaded, Alfred’s family was unable to join him.

In June 1943, Grete, his wife, and their three daughters, Ruth, Eva, and Miriam, were arrested and sent to Westerbork, an overcrowded, rat-infested camp. In 1944, they were transferred to Bergen-Belsen. “To lighten the darkness,” Grete saw to it that birthdays were celebrated, with gifts of a face cloth, a little bag, and a leather brooch made from shoe scraps.

Although religious observance was prohibited at Belsen, Ruth wrote in her diary in 1945 that on Friday nights, as she lay in bed, she prayed that “tomorrow a new day will come,” and the light “will give us the strength to go on living, as it did, and will do, as long as there are Jews on Earth.”

That said, as death seemed all but inevitable, Finkelstein indicates, the Wieners could only hope against hope that the forged Paraguayan passports Alfred had secured for them would result in an exchange for Nazi prisoners.

Allied leaders, Finkelstein reminds us, were aware of the mass murder of European Jews. But as one British Foreign Officer put it, “Once we open the door” to Jews, “a quite unimaginable flood may result.” The Brits were also concerned that sending refugees to Palestine would alienate Arabs.

Reluctant to divert ships to rescue Jews and worried that the circulation of false documents in Latin America was undermining the whole passport system, policymakers in Washington, DC and London also feared that the Nazis would use exchanges to plant spies in their countries.

A school in Prague to make “Jews out of non-Jews,” a British diplomat declared, included “instruction in the Hebrew language and the Talmud, and alteration of features.” His counterpart in the US agreed that “the results of the plastic surgery were remarkable.”

The creation of the War Refugee Board in the US in 1944, Finkelstein reports, meant that, for the first time, the Allies took affirmative action to rescue Jews. The Board had a small staff, however, was often blocked by an unsympathetic State Department, and came too late for Polish Jews.

When World War II ended, Finkelstein tells us, Alfred Wiener, who had been skeptical about Zionism, embraced the idea of a Jewish state in Israel. The Wiener Library initiated one of the first collections of statements by Holocaust survivors.

Although he was “disappointed with the Germany of today,” in 1955 Alfred accepted The Grand Cross of Merit of the Federal Republic, that nation’s highest civilian award. At his request, his eulogy and the psalms and prayers at his graveside were read in Hebrew and German.

Ironically, given everything that had been done to him and his family, Finkelstein concludes, Alfred Wiener died as he had lived – “a self-confident Jew and a German patriot.”

The writer is the Thomas and Dorothy Litwin Professor of American Studies at Cornell University.

‘Two Roads Home’

By Daniel Finkelstein

Doubleday

400 pages; $32.50