According to the Jewish Virtual Library, 550,000 Jews served in the United States armed forces during World War II. There were 38,338 Jewish casualties, while 26,000 Jewish soldiers “received citations for valor and merit.”

But in high-profile TV and film, identifiably Jewish soldiers have been a rare sight.

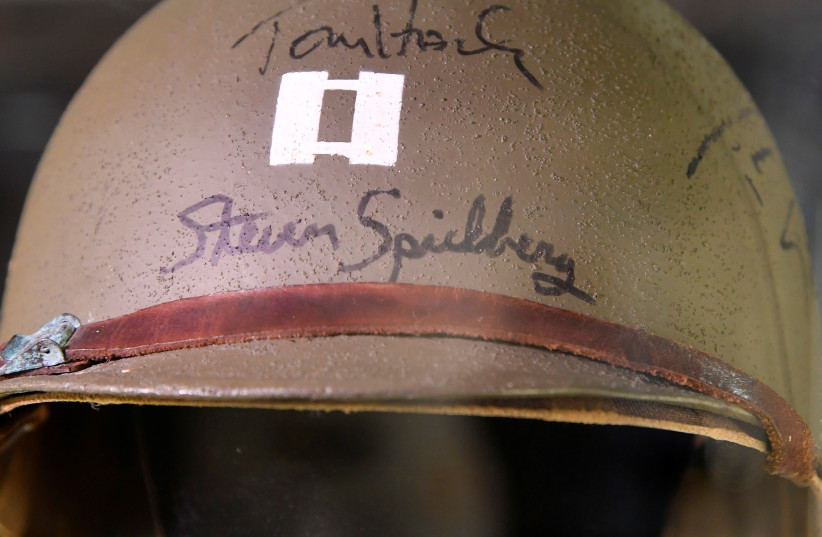

One exception came 25 years ago this week, when Steven Spielberg’s “Saving Private Ryan” hit theaters.

The movie is perhaps best known for its opening sequence, for which Spielberg brutally recreated the invasion of Normandy. From there, the film follows a unit led by Captain John Miller (Tom Hanks) searching through Nazi-occupied France to rescue Private James Francis Ryan (a very young Matt Damon), whose three brothers were all killed in combat.

The characters are played by the likes of Barry Pepper, Jeremy Davies, Edward Burns, Tom Sizemore and Giovanni Ribisi; the Jew of the group is Stanley “Fish” Mellish, a witty wisecracker implicitly from New York played by Adam Goldberg.

Breaking the mould: a Jewish soldier

“Every WWII combat squad seems to have been issued a statistically precise percentage of American types — Irish guy, Italian guy, Jewish guy, farm boy, city boy, old guy, young guy etc — but that trope [in WWII films] was very important in teaching the lessons of teamwork and tolerance,” Prof. Thomas Doherty of Brandeis University, author of the book “Projections of War: Hollywood, American Culture, and World War II,” told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

“It had resonance because so many of the combat squads really were made up of a diverse collection of American types, working shoulder to shoulder and encountering each [other] for the first time,” he added.

Doherty said that his own father, an Irish-American World War II veteran, “didn’t really know any Jews until he served with some” during the war.

Mellish is a proud Jew, as his dialogue makes clear. “Your father was circumcised by my rabbi,” he yells at Nazis in the middle of a gun battle. In one famous scene, Mellish brandishes his Jewish star necklace and taunts German prisoners by saying: “I’m Juden. You know, Juden.”

In an interview with JTA earlier this year, Goldberg said that the horrors of Nazi antisemitism seemed like a distant part of history when “Private Ryan” was made in the 1990s (just five years after Spielberg’s “Schindler’s List”). But more recent events have disabused him of that notion.

“What’s interesting about that, is that… I don’t know how moved I was by that at the time,” Goldberg said of the “Juden” scene while promoting an episode of his CBS procedural “The Equalizer,” in which his character deals with a wave of antisemitic hate crimes. “If you’re doing a good job, and you’re there and you’re present, and it’s 1944… but the truth of it was, it was 1997. And it wouldn’t be until a couple of years later, when I found my name on a white supremacist website, which consisted at that time of a single page… I had no idea how bad shit was, until the internet. And how bad it’s gotten IRL.”

During the years that Donald Trump was president, when Jews on social media received a steep uptick in online antisemitism, Goldberg became known online for tangling with Jew-hating trolls. He told JTA he keeps a folder called “Nazis” on his phone of screenshots of Twitter and other messages from people expressing “an incredible amount of hate” towards him.

Goldberg, who went on to star in the schlocky comedy “The Hebrew Hammer,” said that he is often asked about his turn in “Saving Private Ryan,” which was released when he was 28 years old.

Near the end of the film, Mellish dies, stabbed by a German after a protracted knife fight. Goldberg told JTA that mechanics of his death scene came about from “my facility with a bayonet,” as established during a boot camp training period.

While Spielberg hasn’t spoken much over the years about the specifics of the Mellish character, actor Jeremy Davies told the Los Angeles Times five years ago that Spielberg had determined on the day the scene was shot how exactly Mellish’s death would be presented (which includes Davies’ character of Private Upham freezing up as his friend is slowly killed).

The depiction of the Mellish character wasn’t universally loved. The famed critic Andrew Sarris, writing in the New York Observer, argued that no war movies at the time “even bothered to suggest that the war against Hitler was connected to his persecution of the Jews.” He thought the film implied that soldiers like Mellish, in 1944, wouldn’t have known about the death camps at that time.

In terms of other World War II movies that touched on the Jewish experience of the war, Doherty mentioned “The Young Lions” (1958), “The Pride of the Marines” (1945) and “Gentleman’s Agreement” (1947), in which John Garfield “plays a Jewish combat vet subjected to antisemitism.”

Goldberg looked fondly upon his experience making the film.

“It was a very deeply collaborative experience,” he said. “Steven I think had really made a point of hiring people who he knew were going to give him a lot of feedback, improvisation… there’s a whole scene that was cut from the movie… where we improvised an entire scene in character where we talk about death.”

“It was an experience like no other, and it was a history lesson that I could not have had in any other way,” he added.