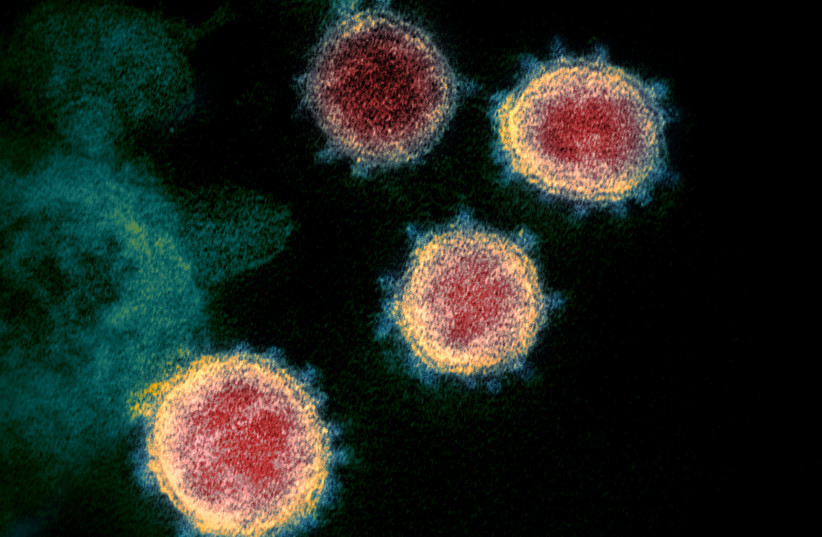

A new novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) variant with dozens of mutations has been detected in new samples collected from patients in Israel and Denmark, with some virologists and data scientists stressing that while it's too early to understand if the variant will spread effectively, it's unique enough to warrant monitoring.

The sample of the variant detected in Israel was recorded on July 31, while the two samples of the variant were detected in Denmark on July 24 and July 31. There are some minor differences between the samples in Israel and Denmark.

Shay Fleishon, executive director at BioJerusalem and a former advisor to the Central Virology Laboratory at Sheba Medical Center, noted that the sample from Israel was collected from a patient who was not chronically ill, with the additional samples from Denmark indicating this variant was spreading and not simply individual cases of extreme mutations in chronically ill or immuno-suppressed patients.

The new variant appears to be descended from the BA.2 variant of SARS-CoV-19, although it also has similarities to other variants and may even be distinct from BA.2, according to Ryan Hisner, a now often cited teacher who is known for being part of a community of coronavirus variant trackers around the world.

Still unclear if the new variant will have any impact

While the new variant has over 30 mutations in its spike protein, it still remains unclear if it will succeed in spreading efficiently or if it will just fizzle out like many other heavily mutated variants.

Hisner noted that the spike protein in the samples is "very different from any other we've seen. This means it will likely evade immune protection from infection and vaccination if it is fit enough to spread widely. But we don't know yet if it's fit enough to do so."

Hisner noted that it is still way too early to say what the impact of the new variant will be, as only three sequences have been found of it so far and it has only been a few days since the sequences were recorded.

In response to questions about the significance of the new variant, virologist Tom Peacock noted that it will be hard to tell until further analysis is done and more samples are collected (if there are more cases) as many of the mutations recorded in the new variant have been recorded in the past, but have usually not succeeded in spreading widely.

Peacock noted that this is the first saltation (a sudden and large mutational change) that's been seen transmitting between patients in a while.

Reduced sequencing hindering monitoring of new variants

Peacock and other variant trackers noted that reduced genetic sequencing of COVID-19 cases has added difficulties to understanding the significance of variants like this new one.

Infectious disease modeler @JPWeiland, who has also been monitoring the spread of coronavirus variants, noted that only 91 cases have been sequenced in Denmark in the past month and only 231 cases have been sequenced in Israel in the past month, meaning that the variant could be more widespread without being detected.

The US, Japan, and the UK have reported slight increases in COVID-19 cases and hospitalizations in recent weeks.

As we near the Fall, scientists have expressed concerns that the decrease in testing and sequencing occurring across the globe will make it harder to monitor new variants.

Christina Pagel, a professor of operational research at University College London, told The Guardian earlier this month that she would call for monitoring practices, including wastewater monitoring, to be increased again ahead of the Fall.

“What worries me most is if we get a repeat of the last winter NHS crisis this winter again, with Covid, flu and RSV all hitting around the same time,” said Pagel. “We are definitely flying near blind.”

Ulrich Elling, a research group leader at the Austrian Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Molecular Biotechnology, called the rate of sequencing around the world “a disgrace” in a recent tweet, noting that only 50 cases were sequenced in Africa, 7.7 thousand were sequenced in Asia, 2.8 thousand were sequenced in Europe, 7.1 thousand were sequenced in North America, and 1,000 were sequenced in Oceania.

“Should we really call that surveillance? How are we supposed to call out relevant variants early? How should we prepare suited vaccinations in time? How should we model epicurves?” added Elling. “The variant "Eris" EG.5.1, a daughter of XBB.1.9.2 with F456L and Q52H, is growing in Europe and worldwide. Together with weaning immunity after a calm northern hemisphere summer, the imminent onset of fall, and school openings, we will see significantly more infections.”

Earlier this month, Maria Van Kerkhove, the technical lead for the COVID-19 response at the WHO, urged member states to “maintain, not dismantle, established COVID-19 infrastructure: Sustain surveillance & reporting, variant tracking, early clinical care provision, vaccine boosters to high-risk groups, ventilation improvements, communication, etc.”