“My life’s mission is to take my post-trauma experience and use it to help others,” states Oren Or Biton, the founder and chairman of the nonprofit Trauma4Good – the association for victims of post-trauma among security forces and rescue teams in Israel. Biton recently received the Presidential Award for Volunteerism from President Yitzhak Herzog for his work on behalf of combat veterans in Israel.

“I was not expecting to receive this award, and I certainly don’t engage in this work to be praised or so that I can be recognized publicly. For me, this award represents an acknowledgment of combat soldiers who are suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and the fact that Israel’s president – the person who is the cornerstone of our political system – is bestowing this award in honor of our efforts to carry out this important work we are doing on behalf of veteran IDF combat soldiers. It means they recognize how important this issue is, and that brings me great joy.”

Biton, 51, who is married and has four children, is completing a bachelor’s degree in Homeland Security and Emergency Management at Beit Berl College. He founded Trauma4Good in 2018 with the goal of assisting IDF combat veterans in dealing with PTSD. “One of the ways I deal with my own post-trauma is by helping others who are dealing with similar issues,” Biton explains.

“I founded Trauma4Good together with the former head of Mossad Danny Yatom, so that we could identify more PTSD sufferers who had not yet been officially recognized as such. You might be wondering why the names of these people were not already in the system. Well, this is because PTSD is an invisible disability.

“People who suffer from PTSD didn’t get their leg or arm amputated – there’s nothing physical that lets you know this person is suffering. It’s a condition where you can talk to a person on the street who is suffering from PTSD about any subject, and still not have a clue what’s happening to them on the inside. Some people experience a mild or moderate level of post-traumatic stress, while others suffer from it quite severely.

“There are post-trauma sufferers who are unable to leave their homes or successfully manage their family life. Some experience suicidal tendencies, and unfortunately, I have also encountered cases in which sufferers have sadly taken their own lives.

“I myself suffer from PTSD, and when my life spiraled out of control, I realized I had two options: I could sink down into an overwhelming abyss of post-traumatic stress and drown, or I could face my problems head-on and turn the situation into something positive. This is why we chose the name Trauma4Good.

“Engaging in this work and addressing combat-related traumas is therapy for me, as well as for all the other post-trauma sufferers, too. Instead of resorting to popping pills and smoking cannabis, I heal by listening and assisting other post-trauma sufferers. This is the greatest therapy for me.”

When others tell you their own harrowing stories, doesn’t this bring up for you your own painful issues that you’ve worked so hard to overcome?

“Yes, it does. I have fibromyalgia, psoriasis, and joint inflammation, all of which are a result of my PTSD. So, when I speak with other PTSD sufferers, sometimes these conditions resurface, but not nearly as much as they did in the past. And I get through these spells much quicker these days, especially since I’m willing to talk about them openly.”

Do you think Trauma4Good is saving lives?

“It says in the Talmud, ‘Whoever saves a single life is considered to have saved the entire world,’ and I believe this wholeheartedly. And don’t forget – we’re not just saving combat veterans, we’re helping their families, too. The divorce rate among combat veterans is exceptionally high since many vets spiral down into substance abuse and alcoholism, which can escalate into problems with the police. Vets’ families don’t suffer any less than the PTSD sufferers themselves, and so we must also give them as much support as possible.”

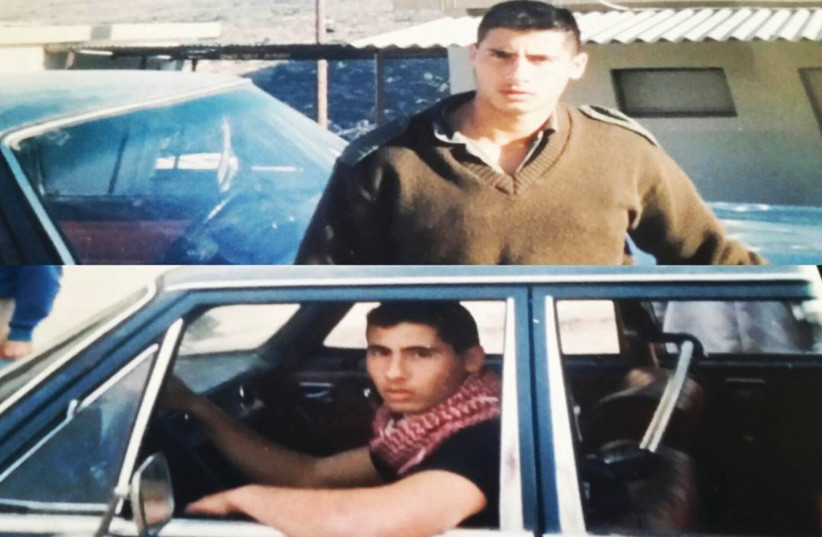

Biton was born in 1971 in the Neve Sharett neighborhood of Tel Aviv, and grew up in Ramat Gan. In November 1989, he joined Israel’s Border Patrol, even though he had wanted to follow in his brother’s footsteps and enlist in the Golani Brigade. “I was excited to enlist in an elite IDF unit,” Biton recalls. “After I completed the commanders’ course, I returned to my Border Control Unit and was stationed in east Jerusalem. This was during a period of time when there were lots of disturbances on the Temple Mount in the Old City. Three months later, I heard that a new infiltration unit of the Judea and Samaria Border Police (Magav) was being formed for special ops.

“I applied, and after undergoing a whole slew of tests and examinations, I was accepted to the unit. I served in combat duty for three years, including as a team commander, and as a sergeant in the infiltration unit. It was an intense and tumultuous period in my life.”

In his 2017 autobiography Powder Keg, Biton describes the complex experiences he underwent as a combat soldier and commander of his unit during the early days of the First Intifada in Judea and Samaria. One of the defining moments of his IDF military service, which Biton details in his book, was the moment when his revered commander, the late Corporal Eli Abram, was killed right before his eyes.

This courageous act saved Biton’s life. “Eli had been on his way to spending a weekend off with his wife and baby, and had asked me to organize a number of troops that would be tasked with eliminating two senior Fatah terrorists in Jenin,” Biton recalls. “I gathered my soldiers and just as we were arriving at the structure, an old Arab woman started screaming ‘Jaysh! Jaysh!’ [‘army’ in Arabic]. As we were sprinting toward the entrance of the building, two terrorists came out and began shooting at us. Eli pushed me out of the way, and he took a bullet to the head and died on the spot. The two terrorists were eliminated. There were body parts and blood everywhere. When I saw Eli’s face, I knew he was dead. It was at that moment that I lost it.

“We had undergone extensive training in this unit, and yet I was still not prepared to see my commander killed right in front of me. The horrors we witnessed and the difficult experiences we underwent during the close-range skirmish had been harrowing. No amount of training can prepare you for such horrors. No human being should have to see such horrific events. We were working around the clock during the First Intifada, and it was inevitable that we’d be exposed to difficult things at some point.”

In 2015, when the TV show Fauda began airing, which follows an undercover IDF unit, Biton’s own experiences, which he had tried to repress, rose to the surface. “I couldn’t even get through the first episode. I had to stop watching the episode four times since I kept experiencing flashbacks,” Biton describes. “The series opens with a wedding scene, where two IDF undercover operatives find themselves almost getting lynched. This was the precise situation my fellow soldiers and I found ourselves in. Every time you embark on a mission, you theoretically understand that you might not make it back home in one piece. And so, when I saw this scene of Fauda, I immediately felt like a 100-ton hammer was pounding on my head.”

After he completed his IDF service in 1992, and returned back home after his post-army trip to New York and Switzerland, Biton joined a team of veterans from elite IDF combat units that was sent to train the Presidential Guard in Congo. Biton had met his wife, Sharon, while traveling in Europe.

“While I was traveling overseas after the army, I would often wake up in the middle of the night from terrible nightmares that would make me vomit,” Biton recalls. “I realized I had a problem, but I’d never even heard of the term PTSD – this was back when it wasn’t a well-known thing. I figured that at some point these flashbacks would just go away on their own. What I didn’t realize is that if you don’t seek treatment, you’re just digging your own grave. It doesn’t get better unless you work with a professional who can help you. This is why we created Trauma4Good – so people don’t need to carry this heavy load on their own.”

Later, Biton moved to Herzliya and opened a hair salon. “One night in 2008, I came home from work. My wife wasn’t home and the kids were sleeping, so I sat down to watch the news on TV. Out of the blue, I began seeing flashbacks from the incident when Eli was killed. I felt like I was right back there, actually re-experiencing the skirmish.

“I felt like someone was choking me, and I heard gurgling sounds. When I opened my eyes, I saw that I had been choking my six-year-old daughter, who had heard me and had come to give me a hug. My wife came home and when I told her what had just happened, she told me: ‘Either we get divorced or you go for treatment.’ And that’s how I set out on my road to recovery. Writing a book and founding Trauma4Good were also important parts of my recovery.”

What actions are you currently taking to keep your post-trauma in check?

“I give lectures to groups and tell them my story. I share my experiences with anyone who is suffering from PTSD. Even the interview I’m doing with you right now is part of my therapy regimen. It is very important to me to raise awareness about this subject.”

In conclusion, what message do you want to convey to others?

“We all experience trauma, but for some of us, the trauma keeps coming back and prevents us from living happy, normal lives. I want people who are suffering from PTSD to know that this is not something you can solve on your own. It will never fully go away, but it is possible to live a normative life with PTSD, as long as you put in the effort and work hard.

“The best way I’ve found to help myself is to help others who suffer from PTSD learn how to deal with it, and to raise awareness. It’s important that people don’t perceive post-trauma as something fatal, but rather as something they can learn to live with.

“I would also like to address the Prime Minister of the State of Israel, Benjamin Netanyahu: In 2021 the Knesset approved the expansion of treatments for post-trauma victims, but this program has not been fully implemented. It is stuck. People suffering from PTSD should not have to pay the price for political ineptitude. We’re not interested in politics, we just want to get on with our lives.

“The State of Israel sent us into battle, from which we returned with serious wounds. All we are asking for is for you to complete the task you have already begun.”

Translated by Hannah Hochner.