In 2017, the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA), in cooperation with the Civil Administration’s Archaeology Department, decided to launch a rescue operation to survey the caves on the cliffs of the Judean Desert. Some decades earlier, in the 1940s and 1950s, those caves had revealed one of the most crucial archaeological discoveries of the 20th century – the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Since then and likely for decades prior to that period, generations of antiquities looters targeted the site – depriving humanity of countless treasures.

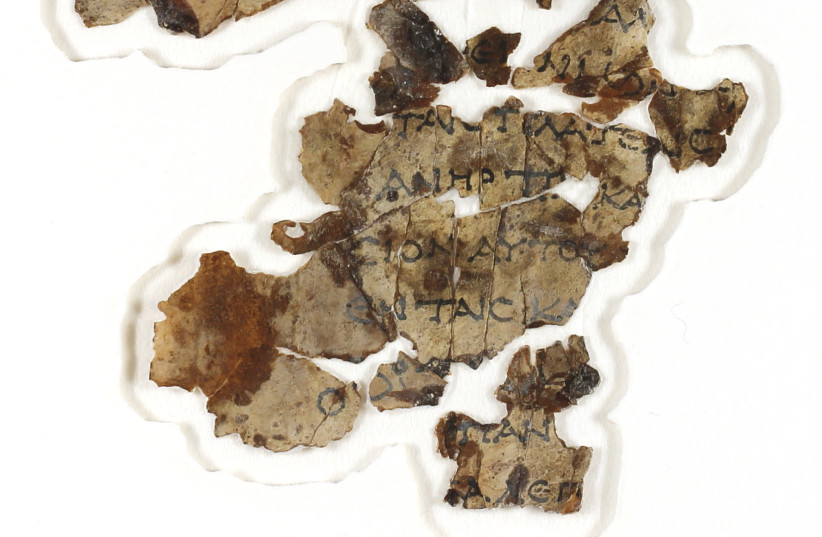

To put an end to the shameful practice, the IAA decided to act and locate remaining artifacts before others would. The efforts paid off: In March, the archaeologists could present to the world not only the first scroll fragments unearthed in about 60 years – parts of the biblical books of Zacharia and Nahum – but also a vast assortment of other finds, including some unprecedented remains from life in the area before history began, including the world’s most ancient woven basket, a skeleton and several other fragments of organic remains.

The endeavor and its results are probably the most crucial developments in Israeli archaeology in the Jewish calendar year that just ended, IAA Chief Scientist Dr. Gideon Avni told the Magazine.

“It is important to keep in mind that the past year has not been an ordinary time for archaeology,” he noted. “Usually, we have some 50 academic expeditions led by universities from all over the world every year, as well as hundreds of foreign volunteers coming to excavate here, including in the digs organized by Israeli universities. None of this could happen because of the pandemic. We had just a very limited number of academic excavations by Israeli universities, in addition to the salvage excavations.”

According to Israeli law, all construction projects must be accompanied by salvage excavations.

The presentation of the results of the Judean Desert expedition has undoubtedly been one of the highlights of the past year, Avni stressed.

“In the end, its major finds have been not related the Second Temple Period, but rather to much earlier times, the Neolithic and Chalcolithic,” he said.

Organic materials usually do not last for such long periods, but the dry weather of the Judean Desert allowed these remains to survive for millennia.

When ancient Jews brought their biblical scrolls to the cave some 2,000 years ago – in this case a hollow known as “the Cave of Horrors” – little did they know that other people had already lived and died there.

THE 6,000-YEAR-OLD skeleton of a child – researchers believe she was a girl between six and 12 years old – was found in a shallow pit hidden behind two flat stones. The body was buried in a fetal position, wrapped in a cloth. The arid desert climate triggered a process of natural mummification, preserving the skin, tendons and even part of the hair.

In addition, the basket stands out as especially impressive – perfectly intact with a capacity of some 92 liters – dating back some 10,500 years, a time when ancient humans did not yet know how to produce pottery.

The archaeologists found evidence that antiquities looters had probably arrived some 10 cm. from the artifact, but they stopped excavating just before reaching it.

They believe that the basket’s owners probably did not live in the cave but rather left it there, possibly to store something, and meant to come back to retrieve it. Whatever prevented them from doing so researchers will never find out, but they were able to determine that at least two people wove it, and one of them was left-handed. Moreover, a small amount of organic material was found inside, and the hope is that further analysis will reveal its contents.

The past year has proven to be very fruitful in terms of progress in research about life in prehistoric Israel.

Speaking to the Magazine, both Prof. Yosef Garfinkel, head of the Institute of Archaeology at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and Prof. Yuval Gadot, head of the Tel Aviv University Department of Archaeology, pointed to some developments in the field that are among their choice of highlights in Israeli archaeology of the past Jewish year.

“Two new academic articles revealed the existence of a new type of early human,” Garfinkel said. “This shed very important light on human evolution.”

In June, a joint Hebrew University-TAU team announced that human remains uncovered during a salvage excavation at the Nesher cement plant near Ramle, dating back some 130,000 years, belonging neither to the Homo sapiens or Neanderthal categories, but rather to a new type of Homo, which they dubbed “Nesher Ramla Homo.”

ACCORDING TO the researchers, the Nesher Ramla person was an ancestor of the Neanderthals and other archaic Asian populations, a view that may radically change assumptions about how ancient populations evolved and interacted. Up until their breakthrough, Neanderthals were believed to have developed in Europe and then spread into other regions, including the Middle East.

“If I have to point to major highlights in archaeology during the past year, I think that more than individual discoveries, I would select broader developments in research which have shed new light on the bigger pictures,” Gadot said.

“My colleague Ran Barkai, for example, published several articles on life of humans over hundreds of thousands of years,” he remarked. The research conducted by Barkai focused on different aspects of nutrition starting from two million years ago.

Multidisciplinary research conducted over the course of several years showed that for most of this time, humans mostly ate meat. Only after the extinction of large animals in several areas of the world – a development itself likely caused by human hunting – did they introduce a higher amount of plants and vegetables in their diet.

However, as humans were forced to hunt small animals in high quantities to make up for the lack of mega-herbivores that provided such large amounts of food, they needed higher cognitive abilities. As a consequence, their brains grew – from a volume of 650 cc to 1,500 cc – enabling them to develop tools they used to become better hunters, including language to share information and better cooperate, as noted in a second paper.

In his third research article, Barkai and other scholars showed that ancient humans used chopping tools to extract bone marrow as early as half a million years ago.

According to Gadot, some recent discoveries in the Jerusalem vicinity helped redefine how we might consider the ancient city, specifically during the end of the First Temple period, in the 7th century BCE.

Experts previously thought that the citadel uncovered in the 1930s at the Ramat Rahel site (today’s southern Jerusalem edge) was in its time not part of the city and, in that, somewhat unique.

However, recently other centers from the same period have been discovered. One was revealed in the Armon Hanatziv neighborhood, which Avni also chose as a highlight of the past Jewish year.

Archaeologists found remains of a prominent structure in the area, including three decorated stone capitals. The rest of the luxurious palace was destroyed, probably to reuse its building materials.

“I think that this discovery, together with the excavations we have been carrying out at the City of David, have completely changed how we can look at the landscape of 7th-century BCE Jerusalem,” Gadot said. “Now we realize how political the landscape of the city was, based on the different structures built in the area, which represented different landmarks of power.”

Another find in the city of Jerusalem, this time at his heart, near the Old City, was selected by Garfinkel.

“I found especially interesting the discovery of evidence of the earthquake mentioned in the Bible.”

WHILE PROOF of the natural calamity from some 2,800 years ago had already been found in other sites – and mentioned in the books of Amos and Zechariah – no remains of it had yet been found in Jerusalem.

Yet in August, the IAA announced that archaeologists excavating in the City of David National Park were puzzled to find a layer of destruction dating back to the eighth century – a time when Jerusalem was not subjected to any invasion or war. They realized there must be another explanation for the destruction of the buildings they were examining as well as for their contents of smashed beautiful vessels, and concluded the cause must have been the biblical earthquake.

One of the few sites where an excavation season was conducted in the summer by a university is also close to Jerusalem, in Tel Motza, along the highway connecting the capital to Tel Aviv.

In 2012, a major temple contemporary to the one in Jerusalem and built in a very similar format was uncovered at the site. Since then, archaeologists have uncovered multiple remains of cultic practices there.

According to Avni, the discoveries of the most recent season, which include figurines and other artifacts, must also be considered among the high points of the past year. Garfinkel also said he has been following the discoveries at Tel Motza.

Garfinkel selected another find which provides essential insights into the relationship between archaeology and the biblical text: An inscription dating back some 3,100 years ago bearing the name of a biblical judge Jerubbaal, featured on a jug uncovered in the excavations at Khirbat er-Ra‘i, near Kiryat Gat.

The researchers emphasized that there cannot be any certainty as to whether the inscription refers to the figure mentioned in the Book of Judges. At the same time, as Garfinkel pointed out, the artifact proves that the name was used during the time when the Bible suggests it was used, proving the text reflected historical reality.

The discovery also shed light on how the alphabet developed and spread: the letters used did not belong to the Hebrew alphabet, but rather to an alphabetic script invented by the Canaanites under Egyptian influence from which the Hebrew alphabet would evolve centuries later.

“This inscription is important also because prior to its discovery we had more ancient inscriptions and more recent ones, but none dating to the 12th-11th century, there was a gap in our knowledge,” Garfinkel explained.

ISRAEL ALSO presents a rich history dating back to later periods, including the Roman, Byzantine and Islamic periods.

One of the earliest churches in Israel – dating back to around 400 CE – was discovered in the Banyas Springs Nature Reserve.

The archaeologists uncovered the remains of a mosaic floor decorated with crosses and other Christian symbols but also including niches, altars and other items indicating that the site was previously a sacred Roman complex open to the sky used for worship of the god Pan.

“This discovery offers us important insights on the penetration of Christianity in the region,” Avni said.

The IAA official also remarked that the past Jewish year saw the completion of another significant project: the renovation and expansion of the Caesarea National Park and its museum.

First established in the fourth century BCE, in the first century Herod selected the settlement to build a port city. The city remained an important center throughout the Roman and Byzantine times. Today Caesarea is one of the richest sites in Israel, presenting remains including a theater, a hippodrome, an aqueduct and a synagogue, as well as the port itself.

However, in a year when the pandemic exacted a heavy toll on Israeli archaeology, Avni also chose to mention a discovery that was halted.

“A few years ago, during an excavation led by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill [they] discovered beautiful mosaics in a synagogue in Hoqoq, in the Galilee,” he said. “This last year they were supposed to be back with a large expedition to continue to excavate the site and fully expose the building. They could not. For more discoveries there, we will have to wait [for] another time.”