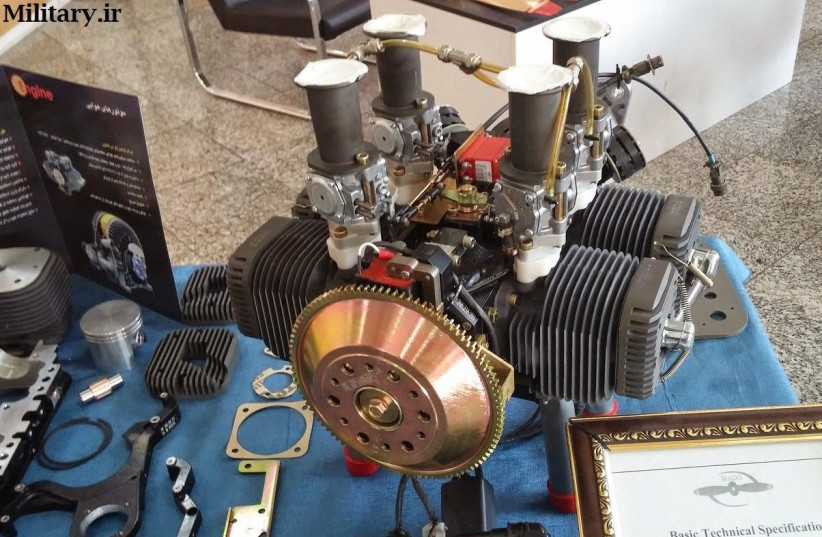

Israeli President Isaac Herzog highlighted the Iranian drone threat at the Atlantic Council event in Washington this week, pointing to the engines of the drones in one slide and referencing a company called “Mado” as the engine maker. The engine used in the Iranian UAVs has been found in wreckage of drone attacks in Ukraine, proving a link to Iran.

“I want to show you two slides that unequivocally prove that Iran and Iranian drones are participating in the war in Ukraine against Ukrainians,” he said. Among the details he highlighted were the drone engines.

“Innocent civilians in Ukraine are being killed and hurt and wounded, and are suffering from Iranian weapons. Iran flatly denied supplying drones to the war against Ukraine,” Herzog said.

Where have these Iranian drones been seen before?

What do we know about the engines and transfers to Ukraine?

The engines and components of drones are a key piece of evidence that can be used to trace where the drones come from. Experts have been examining these for more than half a decade.

This sleuthing began back in Yemen and in the Gulf. For many years, evidence of Iran’s role in trafficking drones and other technology to groups like the Houthis in Yemen, has grown. After Iranian-style drones were used by the Houthis against Saudi Arabia and other countries, the US began to take notice of them.

In 2018, several Iranian unmanned aerial vehicle components were displayed at Joint Base Anacostia-Bolling in Washington, DC.

The Voice of America noted in 2020 that “a small instrument inside the drones that targeted the heart of Saudi Arabia’s oil industry and those in the arsenal of Yemen’s Houthi rebels match components recovered in downed Iranian drones in Afghanistan and Iraq, two reports say.”

One of the reports was by Conflict Armament Research and another was by the UN, which examined the gyroscopes in the downed drones and “a similar gyroscope from an Iranian drone obtained by the US military in Afghanistan, as well as in weapons shipments seized in the Arabian Sea bound for Yemen.”

BY 2021, the US was ready to proceed with sanctions on Iranian manufacturers of drone components. A 2022 article at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy notes that “the Ababil-3 is powered by a four-cylinder Mado MD550 engine, an inferior copy of the German Limbach L550e engine, using Chinese parts and assemblies.

The IRGC-affiliated Oje Parvaz Mado Nafar Co., based in Shokuhieh Industrial Town northwest of Qom, is currently the largest producer of drone piston engines in Iran. In October 2021, the US Treasury Department sanctioned the company and its directors for procuring engines and parts for Iran’s military and drone industry.”

Mado's role in the Iran drone industry

The Mado company and the engine mentioned above is the same one referenced in Herzog’s discussion.

Adam Rawnsley, an expert in drones and a reporter at Rolling Stone, noted in 2021 that the US “Treasury sanctioned the head of the IRGC drone unit who was responsible for the delta wing drone attack on the Mercer Street ship in the Gulf a few months ago.”

He also noted that Yousef Aboutaleni, the CEO of Mado, was hit by sanctions, that at the time the company had showcased its work in Damascus, an ally of Iran, and that Mado was proficient in copying Western products. “You can go through the list of Mado engine products and see the same thing. They’re clearly knocking off Western-model drone engines. The usual (but not exclusive) process was to take a Western model number and a Mado model prefix of MD or MDR.”

Rawnsley documented in 2021 the details about the Mado drone engine trail. They appear to be similar to German Limbach 550E engines for aircraft.

These four-stroke, two-cylinder engines have been made since the late 1980s. Iran’s Mado apparently reverse-engineered the engines, the way Iran has done with many types of military technology that it uses for missiles and drones.

The Iranian company’s CEO was apparently later involved in setting up a company in China. “Iranian military UAV engine company sets up companies in Hong Kong and the mainland, CEO spends some time in Beijing. Chinese company offers eerily similar engines to the one Iranian company offers. One of them shows up in an attack on Saudi Arabia [in 2019],” noted Rawnsley.

The US already went after Mado in sanctions in 2021.

“IRGC Brigadier General Abdollah Mehrabi, as chief of the IRGC ASF Research and Self-Sufficiency Jihad Organization (SSJO), has procured UAV engines for the organization from Oje Parvaz Mado Nafar Company (Mado Company), an entity he co-owns and for which he has served as chairman.

Mado Company and its managing director Yousef Aboutalebi have procured UAV engines for the IRGC Navy and entities supporting weapons development for the Iranian military, including Iran’s Qods Aviation Industries (QAI) and Aircraft Manufacturing Industries (HESA), which is a US-sanctioned company that has provided UAVs to the IRGC,” the US said at the time.

This year, as Iran’s role in supplying drones to Russia has been in the spotlight, the Treasury sanctioned more Iranian entities.

“The US Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) is designating an air transportation service provider for its involvement in the shipment of Iranian Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) to Russia for its war against Ukraine. Additionally, OFAC is designating three companies and one individual involved in the research, development, production, and procurement of Iranian UAVs and UAV components, including the Shahed series of drones, for Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and its Aerospace Force (IRGC ASF) and Navy.”

The role of Mado has now come full circle. It is one of the key points of evidence for how Iran is supplying Russia with drones. But there may be more to this, considering the China connection – and other ways that Iran has succeeded in getting around sanctions and is growing its ties to Russia and China.