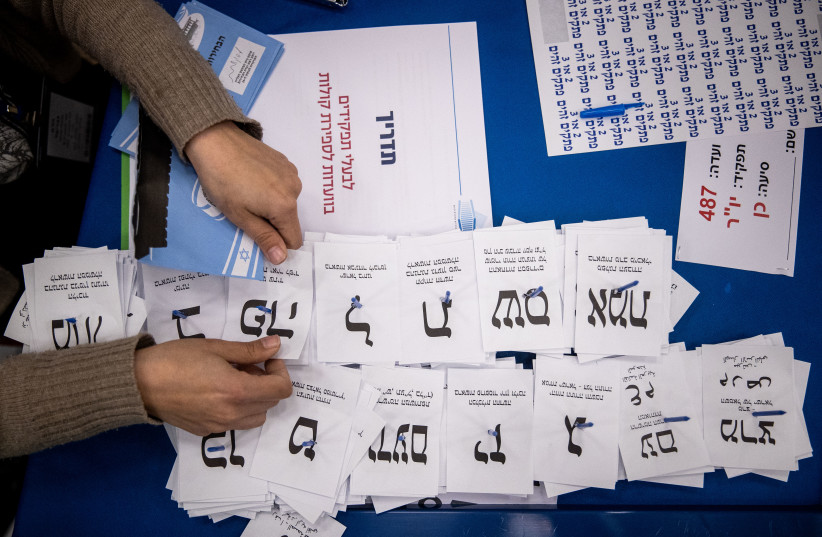

Political arguments are part of the Israeli experience. It’s hard to keep up as the ballots are flying. With a fifth round of elections in less than four years coming up on November 1, there is not much that is agreed on by all.

United on Jerusalem

Perhaps the one subject Israeli Jews do not dispute is the status of Jerusalem as their capital. Hundreds of thousands flocked to the Holy City during Sukkot, some as pilgrims for the traditional priestly blessing at the Western Wall, others as tourists for the cultural activities, culinary experience, the colorful parade and to see sights and sites that cannot be seen anywhere else.

The majority of Israelis were therefore united in their condemnation this week of Australia repealing recognition of even west Jerusalem as Israel’s capital. Israel has at least as much right to determine its own capital city as Australia has to its capital – although I suspect few people in Jerusalem’s crowded streets could name Canberra as that country’s chosen seat of government.

Jerusalem, conquered by King David some 3,000 years ago, is the ancient and only capital city as far as Jews are concerned. Today, it houses the Knesset – the parliament for which Israelis vote in seemingly never-ending election cycles; the Supreme Court, which itself features prominently in electioneering on both the Left and the Right; the Prime Minister’s Residence, which Benjamin Netanyahu was so reluctant to leave and Naftali Bennett chose not to move into even after manipulating his way into the Prime Minister’s Office with just seven seats for his party. It is here that current Prime Minister Yair Lapid and his wife Lihi have found temporary housing in converted accommodation while the main building is being renovated for whoever comes next.

<br><br><br>Elections: Practice doesn’t always make perfect

Jerusalem also houses the President’s Residence, where Isaac Herzog is doing his best to not only heal internal rifts, but to pick up the diplomatic slack. It will also fall to Herzog after the elections to appoint the party leader with the best prospects of forming a ruling coalition.

These elections prove that practice doesn’t make perfect. We remain “polls apart.” There’s still a feeling that many of the politicians are on an ego trip, which is a perilous ride. Instead of having a clear destination and a detailed way of reaching it, yet again we are being treated to reasons why not to vote for X or Y. Once again, the electioneering is dominated by the “Rak lo Bibi,” (Just not Bibi), approach. It’s not an ideology. It’s an obsession. Netanyahu is far from perfect, but telling voters whom they should not to vote for, rather than giving them a positive reason to cast their ballot is a curse, not a democratic blessing.

In 2013, I ridiculed Tzipi Livni for creating an eponymously named party in her own image, but maybe she was onto something. Those elections, like the current ones, were about Freudian id rather than ideology. Parties have agendas rather than platforms and virtual supporters rather than structural support. Without clearly defined beliefs, MKs hop between parties seeking the best opportunities in a place they can temporarily call home.

Many parties are defined by the person who leads them. People talk of voting for “Bibi,” “Lapid,” “Gantz,” “Ben-Gvir,” “Smotrich,” “Liberman,” and so on.

Labor, currently led by Merav Michaeli, is one of the few lists still widely referred to by its name rather than its leader’s moniker. Given the frequency with which the party has changed its No. 1, that might be understandable. A mirror situation exists with Ayelet Shaked – it’s easier to remember her name than whatever the party she leads is being called this week. Ditto: Benny Gantz.

When the music stopped in the political party game version of musical chairs, Shaked landed up back with Habayit Hayehudi, having been through the New Right, Yamina, and Zionist Spirit and perhaps something I missed when I took a day off. Gantz has led lists under the names Hosen L’Yisrael (Israel Resilience), Kahol Lavan (Blue and White), and currently Hamahaneh Haleumi (National Unity).

Even Meretz under Zehava Galon’s redux leadership is using the slogan: “I’m back.” Her platform, such that it is, is firmly in the Just not Bibi camp and seems to be more concerned with Palestinian rights than those of the Israeli voters. The same could be said for the Arab parties, suffering from internal divisions and tensions.

<br>Arab parties and the violence problem

The Arab parties are free to run, but what they are running or standing for is also in dispute: They have not served their own voters particularly well. The exception being Ra’am (the United Arab List), whose Mansour Abbas took a strategic decision following the last election to join the coalition. Whether this gambit will pay off at the polling booth remains to be seen.

The problem of violence within the Arab sector is probably the most important issue on the Arabic-speaking voters’ minds. This needs to be translated into action within the community, rather than just blaming police and government inaction as so far seems to be the case.

Personal security, especially in mixed Jewish-Arab towns, is high on the agenda in general, or should be. The rioting that broke out and the roads that were blocked in the North and South as rockets from Gaza rained down during Operation Guardian of the Walls last year marks a watershed moment. Many have managed to move on, but that doesn’t mean all is forgotten – or forgiven.

<br>Rise of the far right in Israel

The phenomenal rise of the far-Right’s Itamar Ben-Gvir in opinion polls can be attributed in large part to those riots with additional fuel from the recent string of terror attacks. Whereas Meretz leader Galon on Saturday said that Gantz as defense minister “needs to restrain” IDF soldiers and complained of the easing of open-fire regulations, Ben-Gvir is gaining political ground by vowing to restore a sense of security and tackling terrorism more firmly.

There is a whole lot of middle ground which is being missed even by the so-called Center. It is a safe bet that people everywhere worry about the same basic needs as they did even before the birth of democracy: food and shelter. And no politician anywhere is going to mount a campaign against education and healthcare. Nor should a wise politician anywhere under the sun – which seems to get hotter and hotter – reject the need for environmental protection. This should be beyond politics, although for some strange reason has been taken over by the Left.

Despite the political uncertainty, Israel is better off than many western countries – the COVID vaccination roll-out under Netanyahu has helped keep the coronavirus pandemic under control and the economy has bounced back; the main focus of the discussions on energy concentrate on the wisdom, handling and legitimacy of the Lapid deal with Lebanon (with American prompting), but Israel is not expecting the same crisis as elsewhere following the Russian invasion of Ukraine; there is rising inflation and soaring housing prices, but the currency remains strong. A quick look at Lebanon suffices to know that the neighbor’s grass is not always greener.

Changing the electoral system itself should be a priority. The challenge is not only to create a coalition, but to maintain it. Political science as an art. Politicians should remember these are elections, not a ratings war. There are serious, real life-and-death issues at stake.

Two weeks is a very long time in Israeli politics, let alone when they precede another election. It’s impossible to make predictions after the seemingly impossible happened in the last elections when Bennett with his handful of seats, elected on a right-wing platform (or at least, right-wing slogans), ended up creating a left-leaning coalition that included an Arab Islamic party.

Perhaps one of the few things Israelis can agree on is the need for electoral reform. Sadly, what form that should take is far from a consensus issue. The politicking can make your head spin. No wonder it leaves voters feeling nauseous no matter which party they support – or whom they are voting against.

liat@jpost.com