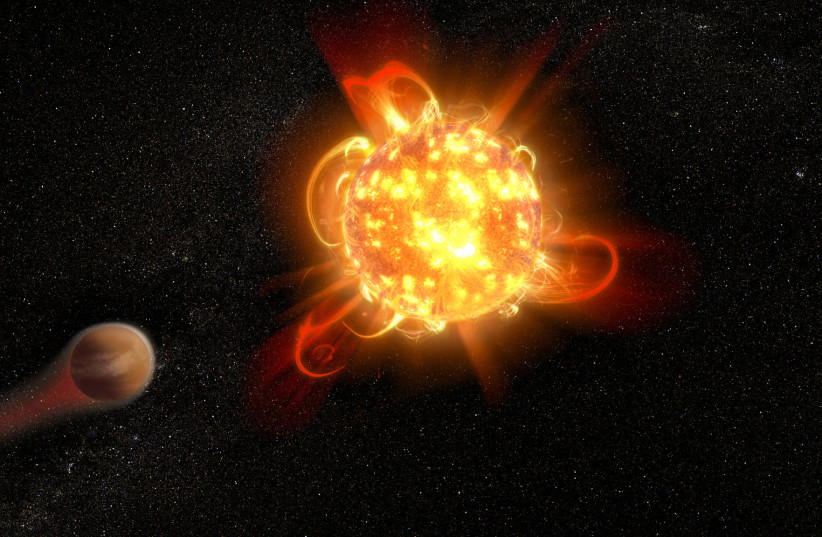

Dying stars expand into a million times their original size, swallowing anything - including entire planets - in its range. Scientists have been able to observe stars before and after this dramatic expansion, but only this year were they able to catch a hungry star in action.

A report published on Wednesday in peer-reviewed journal Nature detailed the process of planetary engulfment and its observation via bright, long-lasting infrared emissions from the dying star.

“We were seeing the end-stage of the swallowing,” says lead author Kishalay De, a postdoc in MIT’s Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research.

What scientists initially observed was an outburst from a star that became more than 100 times brighter over the course of 10 days before fading quickly. This burning-hot flash was followed by a colder, longer-lasting signal. This is what led researchers to the conclusion that they must have witnessed a star engulfing a nearby planet.

According to the study, the planet was likely similar in size and composition to our solar system's Neptune or Jupiter.

“We are seeing the future of the Earth,” De said. “If some other civilization was observing us from 10,000 light-years away while the sun was engulfing the Earth, they would see the sun suddenly brighten as it ejects some material, then form dust around it, before settling back to what it was.”

The phenomenon was initially observed in May 2020 in data collected by the Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF) in California. Its infrared emissions followed an unusual pattern, prompting deeper investigation.

“One night, I noticed a star that brightened by a factor of 100 over the course of a week, out of nowhere,” De recalled. “It was unlike any stellar outburst I had seen in my life.”

Digging deeper, researchers in November 2020 incorporated data from the Keck-I telescope in Hawaii, which take spectroscopic measurements that scientists can use to determine the chemical composition of a star. However, the new information only further complicated the situation.

“These molecules are only seen in stars that are very cold,” De said. “And when a star brightens, it usually becomes hotter. So, low temperatures and brightening stars do not go together.”

The final piece of the puzzle

In the Spring of 2021, researchers were able to look at infrared data taken on the phenomenon from the Palomar Observatory in San Diego, California.

“That infrared data made me fall off my chair,” De said. “The source was insanely bright in the near-infrared.”

The numbers were consistent with the explosion of a red nova star, but the extremely low luminosity levels were not at all characteristic of such a phenomenon.

Finally, the team was able to add data from NASA's infrared space telescope, NEOWISE. From the newly-compiled data set, they were able to determine that the energy released by the star since the outset of the explosion was shockingly small.

“That means that whatever merged with the star has to be 1,000 times smaller than any other star we’ve seen,” De said. “And it’s a happy coincidence that the mass of Jupiter is about 1/1,000 the mass of the sun. That’s when we realized: This was a planet, crashing into its star.”

At this point, scientists were able to put together all the pieces of the puzzle and explain the phenomenon. The initial bright, hot flash was the planet's being pulled into the star's expanding atmosphere. The ensuing chill came from the outer layers of the star being stripped away as the planet drove into its core.

“For decades, we’ve been able to see the before and after,” De said. “Before, when the planets are still orbiting very close to their star, and after, when a planet has already been engulfed, and the star is giant. What we were missing was catching the star in the act, where you have a planet undergoing this fate in real-time. That’s what makes this discovery really exciting.”