Few if any Australian Jewish families have given as much of themselves, for the benefit of their local, federal, and international Jewish communities, as the Leiblers.

Other well-to-do Australian Jews may have given more money than have the Leiblers, who have been far from stingy, but no other Australian Jewish family has collectively held as many leadership roles as they have.

Staunchly Zionist, many of them now live in Israel, and some have children in the army.

For more than half a century Leiblers have either headed or held executive positions in various Australian Jewish community organizations, Israeli enterprises, and world Jewish associations.

Last week, Zionist Federation of Australia president Jeremy Leibler, a third-generation Australian Zionist leader, helmed a solidarity delegation that came to Israel. Among the members of the delegation was Leibler’s nephew Gabe Max, who is a university student leader and chairs the Australian Zionist Youth Council.

An affluent family that made its money in diamonds, international travel, and the practice of law, the family also boasts three generations of lawyers. “A law degree always comes in handy,” says Max.

Several of the Leiblers are practicing attorneys, while others have law degrees, but are engaged in different professions.

Jeremy Leibler, like his father Mark before him, is both a successful lawyer and president of the Zionist Federation of Australia.

There was no pressure on him to become either an active Zionist or a lawyer, he says. “There was no explicit process. Just an example” that he saw in his family, and which gave meaning and purpose to their lives. It was simply something in his DNA coupled with the fact that he has a close relationship with his father in whose footsteps he chose to follow.

Growing up in what used to be the religious Zionist environment, there was a sense of responsibility for the Jewish future after the Holocaust.

There was a unique formula to connect to Israel and Jewish values related to Israel, he says, “but this is now out of date.”

Asked to explain the family’s strong commitment to Jewish life and Zionism, Leibler says that like many Melbourne Jews, his father and uncles grew up in the shadow of the Holocaust, which has also affected him. That said, Leibler doesn’t want Jews to be defined by the Holocaust. He would rather have Jews defined through the continuation of positive challenges than as survivors of negative ones.

On a Jewish community per capita ratio, Australia, particularly Melbourne, had one of the greatest intakes of Holocaust survivors, and its numerous landsmanschaften organizations of Jews from specific countries and cities were dominated by Holocaust survivors as well. There are Holocaust museums and monuments, and Holocaust history is taught in the network of Jewish Day Schools. It is almost impossible for a child growing up in a Jewish community in Australia to be ignorant of the Holocaust.

Though geographically distant from the rest of the Jewish world, Australian Jews have been actively associated with Israel since before the establishment of the state. Some, as members of the Australian army, even fought here against the Turks during the First World War, and there were Jews among the Australian forces in the Middle East during the Second World War.

In 1948, Australian members of the Habonim Zionist youth group were among the founders of Kibbutz Kfar Hanassi in the Upper Galilee. Today, many Australian Jewish students spend their gap year in Israel, or come to the country as visiting members of Zionist youth movements.

In Melbourne alone, the Jewish Community Council of Victoria is the umbrella organization representing more than 50 Jewish organizations, several of which are affiliated with Israeli universities, hospitals, and cultural institutions.

A short list of Leibler family accomplishments: Jeremy Leibler and his father have already been mentioned. Jeremy’s grandfather Abraham Leibler was president of the Victorian Jewish Board of Deputies. His paternal grandmother Rachel Leibler was the founder of the Australian branch of Emuah, the religious women’s Zionist organization. His late uncle Isi Leibler, who spearheaded the Let My People Go campaign on behalf of Soviet Jewry, was president of the Executive Council of Australian Jewry and vice president of the World Jewish Congress. After moving to Israel, Isi Leibler’s wife Naomi was elected world president of Emunah.

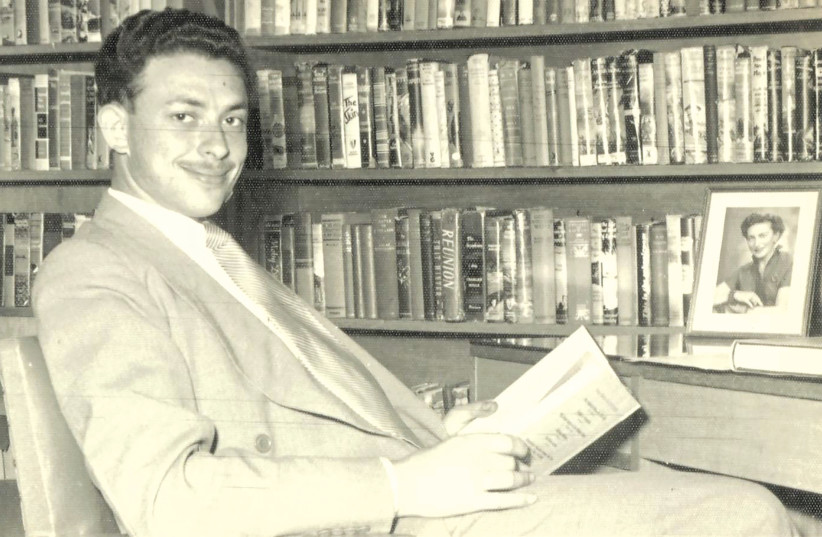

Rachel Leibler and her young son Isi left Belgium just in time to escape the clutches of the Nazis. Her husband had preceded her, and soon after the family settled in Melbourne, he became a significant force in the Jewish community.

Unfortunately, he died at an early age, leaving Rachel to battle on her own with three young sons, all of whom became prominent in Bnei Akiva. The two younger boys, Mark and Alan, were also students at Mount Scopus College, a Jewish day school, now celebrating its 75th anniversary.

As is the case in several countries, while the government is not antisemitic, and Australia was among the first countries to establish diplomatic relations with Israel, there are sectors of the population that are rabidly antisemitic and others that behave with political correctness but exude an aura of antisemitism and anti-Israelism – more so, since the Hamas massacre on October 7.

Asked about this, Leibler replies: “The world has changed for the Jewish community. Antisemitism is simmering in the wider progressive space. After October 7, there was silence from many of our friends and colleagues.”

The silence was also evident in numerous organizations that are generously supported by Jewish philanthropists.

Australian Jews are major patrons of the arts, education, sports, and medical facilities.

Some are now following the example of American Jewish philanthropists who have suspended their giving to universities that do nothing to prevent antisemitism on campus.

Despite the immense service that Jews have given to Australia – two Australian Jews, Sir Isaac Isaacs and Sir Zelman Cowen, served as Governors-General of Australia, another Jew, General Sir John Monash, was commander of the Australian Corps during the First World War, and was considered one of the best generals in the Allied Forces, many other Jews have risen to prominent positions in various fields, and the current Attorney General Mark Dreyfus is Jewish – antisemitic incidents take place daily.

Antisemitism is alive and well on the right as well as the left. Leibler cites swastikas drawn on synagogues, Jewish institutions, and Jewish businesses.

“It’s like the boycott of Jewish businesses in Germany in the 1930s,” he says.

Some television anchors, when interviewing Jewish community leaders, are openly antisemitic in what Leibler terms “a bizarre alignment with the Far Left.”

But there is a bright spot: The newspapers condemn antisemitism, says Leibler, and in surveys, most Australians blame Hamas for the current blaze of hostilities between Israel and Gaza.

Under Palestinian pressure

Even so, he notes, the Albanese government is under a lot of Palestinian pressure, and the prime minister, the foreign affairs minister, and the defense minister have all met with representatives of Palestinian families.

In addition, there have been pro-Palestinian rallies in Jewish residential areas, and a letter accusing Israel of genocide has been widely circulated.

The growing antisemitism and anti-Zionism in Australia poses a particular challenge for the Jewish community, in that it’s more than battling against anti-Jewish racism.

“We cannot define ourselves by the Holocaust, and must not fall into the trap of being identified by antisemitism,” Leibler emphasizes. “We need to adapt to an Australian Jewish identity.” He perceives recent developments as an awakening.

In his view, it is important to bring Australian Jews to Israel to help them better understand the rationale of being linked to the Jewish homeland.

Although he has been immersed in Zionism all his life, the 44-year-old Leibler nonetheless felt that there was a difference between Diaspora Jews and Israelis. But, as he discovered on his most recent visit last month, that the similarities far outweigh the differences. Together with members of his delegation, he spent an evening at the Orient Hotel in Jerusalem, where some of the displaced residents of the south are presently accommodated, and discovered when sitting around a table with them, that they had many shared sayings, habits, and traditions.

“It was one of my most profound Jewish experiences,” Leibler says.

Aware of and sensitive to the divisiveness that split Israeli society before October 7, Leibler is hopeful that the national unity which over the past two months has transcended religious, political, and ethnic differences, will continue to serve as a guideline to Jewish communities in Israel and around the world.

“We cannot go back to the divisions brought on by judicial reform,” he insists. “What happens in Israel, impacts [us all].”