Some antiviral medications might be able to improve the condition of patients infected with monkeypox, according to a new retrospective study published amid the ongoing spike in monkeypox cases throughout the world.

The study, published in the peer-reviewed academic journal The Lancet Infectious Diseases, examined seven monkeypox cases found in the UK between 2018 and 2021, which represented the first instances of hospital transmission and household transmission outside Africa, where the disease is endemic.

The study also noted the response of patients to the use of antiviral drugs tecovirimat and brincidofovir in trying to treat monkeypox.

<br>What is Monkeypox?

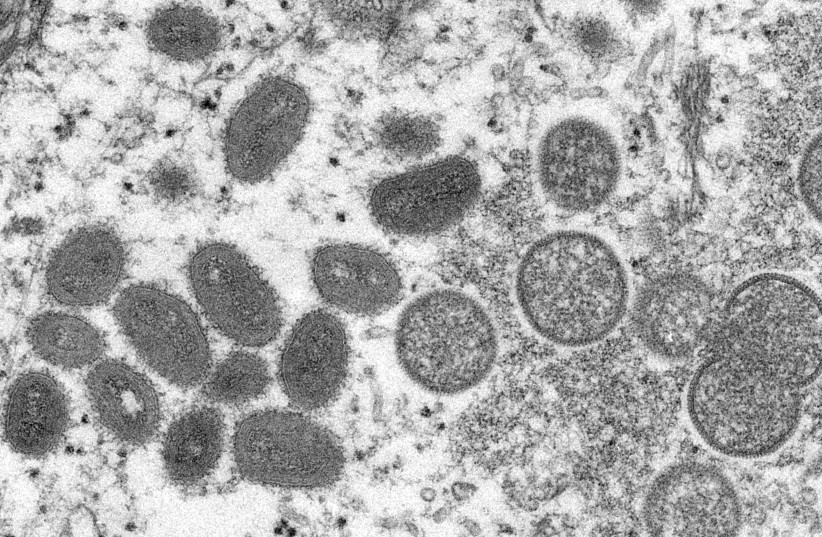

Monkeypox is a disease caused by the monkeypox virus, itself a zoonotic disease that can infect certain animals, such as people. It was first identified in the 1950s and the first human case was confirmed in 1970.

It is primarily found in West Africa and Central Africa but has on multiple occasions spread abroad.

The disease itself has a very low mortality rate, unlike its relative, smallpox.

As is the case with smallpox, monkeypox produces similar skin lesions as well as rashes and blisters. Also experienced are flu-like symptoms.

The flu-like symptoms tend to come first, which sees fatigue, back pain, muscle aches, fevers, severe headaches and swelling of the lymph nodes — something the WHO notes is a distinctive feature of monkeypox.

This initial period, the invasion period, lasts briefly, and the skin eruptions manifest within 1-3 days after the fever does.

These skin eruptions are usually focused on the face most of all, but they can also be present on the palms of hands, soles of feet, eyes and genitals.

However, except for using the smallpox vaccine as a preventative measure, there are no licensed treatments for monkeypox. And despite its low mortality rate, symptoms usually last around 2-4 weeks.

<br>The antivirals

While there are no agreed-upon treatments for monkeypox, the two antivirals in question, brincidofovir (sold under the brand name Tembexa) and tecovirimat (sold under the brand name TPOXX, among others), have been approved in the US as a smallpox treatment. Further, these drugs also show a considerable degree of efficacy in treating monkeypox in animals.

However, the efficacy of these drugs has not properly been studied in human trials.

<br>The study

Of the patient cases examined in the study, some were treated with brincidofovir and one was treated with tecovirimat.

The study then examined what happened to them over the course of their stay in the hospital.

<br>The results

Overall, treatment with Brincidofovir did nothing to improve the patients' conditions.

In fact, all three patients treated with brincidofovir developed deranged liver enzymes (a side effect of the drug) during treatment, which affected the course of the treatment itself.

The patient treated with tecovirimat, however, was another story. This patient's condition began to improve, having only been hospitalized for 10 days and experiencing a shorter duration of viral shedding and illness. All of this was without any adverse side effects.

<br>So what do these results mean?

On the surface, it means that further study into tecovirimat as a possible treatment for monkeypox is worth looking into.

In fact, an expanded program by SIGA Technologies and the University of Oxford to use tecovirimat to treat monkeypox in the Central African Republic, where the disease is endemic, was announced in 2021.

However, there are multiple issues with this study.

First, there is the fact that the sample size was so small. This itself is understandable as it is the result of monkeypox being so rare outside of Central and West Africa.

Indeed, only one patient was actually treated with tecovirimat at all.

Secondly, regarding the use of brincidofovir, it is possible that the results could have been different if treatment began earlier, or if the dosing schedule was different. After all, it has shown positive results when used in some animals.

However, with monkeypox cases on the rise, further research into treatments are essential - particularly as the exact means of transmission being used in the current outbreak aren't fully understood.