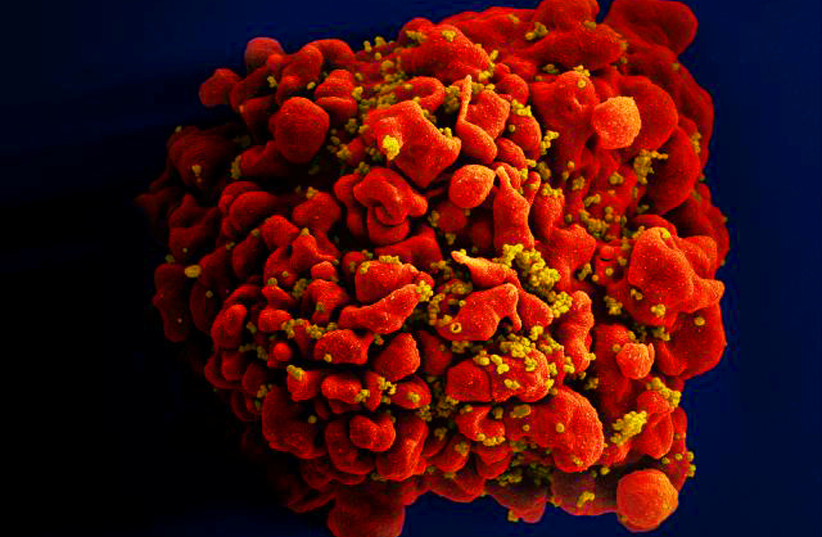

Nearly 40 million people around the world are currently living with HIV (human immunodeficiency virus), and tens of millions of people have died of AIDS-related causes despite 40 years of intensive research in which scientists have not succeeded in finding a cure for the disease.

While many people living with HIV or at risk for HIV infection lack access to prevention, treatment, and care, large numbers take an AIDS “cocktail” of drugs daily to keep the disease under control.

People with HIV experience a flare-up of the virus only a few weeks after stopping treatment. An international team of researchers, led by scientists at Aarhus University and Aarhus University Hospital in Denmark may have moved an important step closer to a medication-free existence for the millions living with HIV today.

Last year, the researchers showed that people who had just been diagnosed had a stronger immune response against the virus and lower levels of the virus in their blood when they were given monoclonal antibodies against HIV, along with starting regular medical treatment. Monoclonal antibodies against HIV are very specific and highly potent antibodies that are synthetically produced in large quantities and are used for experimental treatment.

In a new study, recently published in the prestigious journal Nature Medicine under the title “Impact of a TLR9 agonist and broadly neutralizing antibodies on HIV-1 persistence: the randomized phase 2a TITAN trial,” the researchers have shown that patients who have been on treatment for years also benefit from this therapy.

Specifically, the antibody treatment allowed the study participants to suppress the virus for more than three months. While some of the participants continue to spontaneously suppress HIV for more than 18 months after their regular HIV treatment has stopped.

Prof. Ole Schmeltz Søgaard from the clinical medicine department at the university – who was the lead author and had collaborators from his university and others in Norway, Australia, and the US – said he hoped the new findings will bring us closer to a cure. “It is one of the first placebo-controlled trials conducted on humans, where we have shown a way to boost the body’s own ability to fight HIV even when standard treatment is paused. We therefore see the study as an important step towards a cure,” he said.

In the trial, study participants from three countries were randomly divided into four groups, one of which took the drug named lefitolimod, an investigational drug being studied as part of a strategy to cure HIV infection that belongs to a general group of HIV drugs called latency-reversing agents. It was designed to enhance immune cell response against the virus.

Another group received two monoclonal antibodies against HIV that can eliminate the virus and strengthen the cells’ immune system. The third group received standard treatment without experimental medication, while the fourth group received both types of experimental medicine.

Monoclonal antibodies significantly delayed reappearance of the virus

The results of the study are very encouraging, stated Dr. Jesper Damsgaard Gunst from Aarhus University Hospital, who is also one of the lead authors of the study. “Unfortunately, there was no extra benefit from lefitolimod, but our study shows that people with HIV who receive monoclonal antibodies before pausing their regular HIV medication experience a period of about three months before the virus reappears.

Additionally, the immune system in a third of those who received monoclonal antibodies can partially or completely suppress the virus, even after the monoclonal antibodies have left the system,” he explained.

Despite the remarkable results of the study, there is still a long way to go before a cure is available, Schmeltz Søgaard conceded.

First, the researchers need to optimize the treatment and enhance its effects, so more trials are on the way. “The hope is that we will gradually improve our experimental treatment strategy to a level where the effect of our treatment is that up to 50%, 70%, or even 100% of patients become medication-free and neither relapse nor can infect others. If we can achieve that, we will have developed a cure for HIV that will change the lives of the tens of millions of people living with the disease today.”

The research group is now recruiting participants for a large UK-led clinical trial funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, which will also test the effectiveness of two monoclonal antibodies against HIV. The group is also planning a larger study across Europe to optimize experimental treatment with monoclonal antibodies.

Søgaard Schmeltz has high expectations for the new trials. “Our hypothesis is that the optimized treatment will have an even stronger effect on both the virus and patients’ immunity. In this way, we hope to improve the immune system’s ability to permanently suppress the remaining virus in the body,” he concluded.