On a sunny afternoon at Pembroke College, Oxford, I had the pleasure of interviewing Natan Sharansky, who is the former head of the Jewish Agency and the current president of the Institute for the Study of Global Antisemitism and Policy (ISGAP) on the importance of combating antisemitism on campuses and within academia. Sharansky sums up the common struggle of several, if not most, Jewish students on Western campuses today: “Many Jewish students on campus feel they have to choose between their connection to Israel and staying as an accepted part of student society.”

This choice that Mr. Sharansky proposed in his interview is the same one I had to make while completing my undergraduate degree in small-town Halifax, Nova Scotia. The same decision led to me working full-time towards combating antisemitism on university and college campuses.

ISGAP's leadership management

Under the leadership of ISGAP management, I had the pleasure of co-organizing two events over the summer. First, an international conference on Jew Hatred at Cambridge followed by a two-week Summer Institute for Curriculum Development in Critical Antisemitism Studies at Oxford. Throughout the events, I had the privilege of learning from some of the world’s greatest scholars of antisemitism.

The lectures covered a wide range of topics, from antisemitism in Southeast Asia to human rights and lawfare, but the presentations I was most drawn to focused on the indoctrination of antisemitism in social sciences, particularly intersectionalism.

As a young Jewish immigrant from Brazil studying in Canada, I entered the liberal arts secure that my core values as a staunch zionist, feminist and progressive would be accepted. However, the more outspoken I became about Zionism, the less welcomed I was by my peers and professors.

The choice between Israel and acceptance presented itself to me in my final year of university, when I decided to branch my areas of study into social sciences. I met with an adviser who had been recommended to me by one of my friends due to their kindness and helpfulness in mapping out courses. In my meeting with her, I explained that I wanted to focus on certain topics to prepare myself for the master’s degree. I wanted to complete in Israel the following year.

Rather than helping me find adequate classes, the adviser provided me with a list of readings and courses she and other professors in the department taught about the Palestinian cause. Before I exited her office, she warned me not to tell the powerful Jewish lobby in Canada about the meeting, otherwise, they would hunt her down and try to destroy her career.

How normalized must antisemitism be, that upon the first meeting with a student, a university professor felt comfortable enough to make accusations about the powerful Jewish lobby in Canada?

Professor William Kolbrener from Bar-Ilan University, who presented and participated in both events, details why antisemitism has become integral in intersectionality: “It is not just an accidental or incidental exclusion [within intersectionality], the exclusion of the Jew is the basis of the thought. Anti-Zionism is the tell for being progressive.”

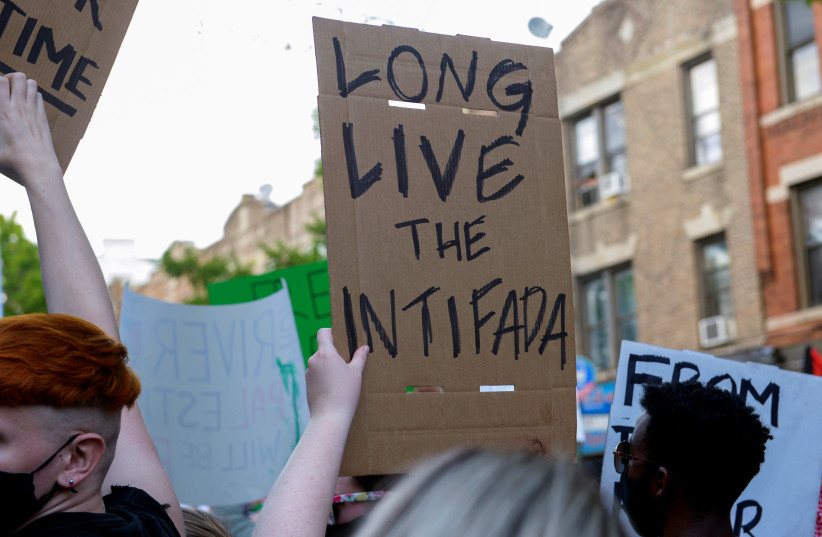

Jew-hatred in colleges and universities

If Jew hatred is the unifying ideology within intersectionality, which currently dominates the forefront of mainstream social justice movements, presenting the pervasive antisemitic literature responsible for the foundation of these ideologies becomes a duty in the name of righteousness.

That meeting to select my courses was the first of many tests that my professor used to assess whether my beliefs were malleable enough to be fixed. Unsurprisingly, a few weeks into the semester, following a statement declaring any form of a Jewish State is as racist as Nazi Germany, she presented me with an ultimatum: “This is a course about Palestinian liberation, are you able to stay in this class?”

I had to choose between hiding my Zionism and Jewishness or making my beliefs as loud as possible, despite the things I would lose by doing so. I realized that there was no amount of social justice movements I could align myself with to prove to that professor and all others like her that I was a good person. The moment I declared my support for the existence of Israel, I became a racist in their eyes.

Author of Jewish Pride and dear friend Ben M. Freeman discussed, in an interview at the ISGAP-Woolf Institute international conference, how to move forward: “My values are not going to be changed despite the rhetoric about Jews in these [progressive] spaces. I am also going to demand that Jews are included or even if we are not included I am going to continue my work. I am not going to wait for the wider movement to see us as being part of their struggle.”

The writer holds an M.A. from Reichman University, and is a research and programing coordinator at the ISGAP.